Argentina’s economy

It’s cold outside

A battle over utility bills is Mauricio Macri’s first big crisis

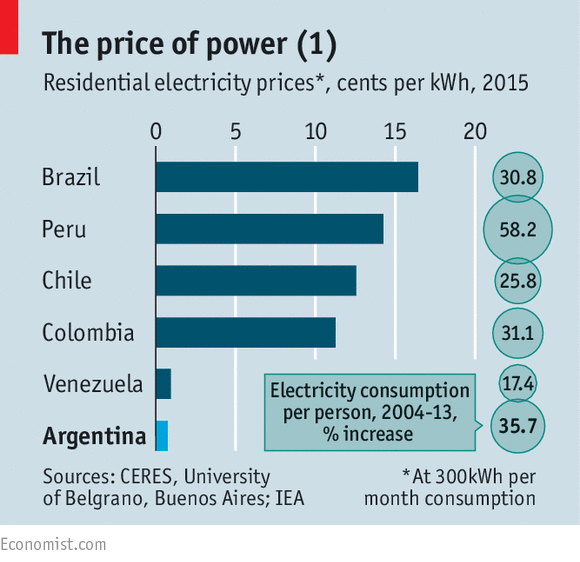

THE most populous parts of Argentina are stifling in summer and bone-chilling in winter. The Kirchner family, which ruled for a dozen years until 2015, kept the cost of comfort low. An earlier government had fixed the price of electricity and natural gas in 2002 to help the economy out of a slump; the Kirchners barely raised it. As a result, Argentines pay a fraction of what their neighbours do for energy (see chart).

But they have paid in other ways. Energy subsidies jumped from 1.5% of government spending in 2005 to 12.3% in 2014. Partly because of such largesse, the budget deficit was a worrying 5.4% of GDP last year. Because energy is cheap, consumers use it with abandon; utilities lack cash for investment. Summer blackouts can last for hours. Mauricio Macri, who succeeded Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as president in December, said the energy crisis was the most complex of the “many bombs” she had left for him. Defusing it is proving to be perilous.

Advertisement

|

Soon after Mr Macri took office the energy minister, Juan José Aranguren, said he would chop the $16 billion subsidy bill in half. Gas tariffs would quadruple for most consumers; those for electricity would increase sixfold. The higher bills landed in consumers’ post boxes in June, during Argentina’s coldest autumn in 60 years. A backlash followed. Pot-banging protests, called ruidazos, took place across the country on August 4th. A few days later thousands of pot-bangers marched to the Casa Rosada, the presidential palace. Two courts have blocked the tariff rises. The final decision now rests with the supreme court.

The government cannot afford to lose. The price increases are a vital part of Mr Macri’s plan to restore confidence in an economy undermined by years of reckless spending, self-defeating price and regulatory controls, and economic nationalism. He began his presidency by allowing the peso to devalue, removing taxes on food exports and striking a deal with holders of debt on which Argentina had defaulted.

Unsurprisingly, the remedy has been painful. The peso’s drop pushed the inflation rate to more than 30% even before utility bills went up. Growth, private employment and manufacturing have fallen since Mr Macri came to office. The IMF expects the economy to shrink by 1.5% this year. Argentina’s deal with bondholders has yet to trigger the surge in foreign investment that the president promised would follow.

The government’s clumsy handling of the price rises made the backlash worse. Alfonso Prat-Gay, the finance minister, airily dismissed them as “the cost of two pizzas”. Mr Macri upbraided energy gluttons. “If you’re in a T-shirt and bare feet around the house, you’re using too much,” he lectured. On Twitter, indignant Argentines posted videos of themselves listening to his speech dressed for Arctic conditions.

The government has tried to placate voters without abandoning its policies. “We got it wrong,” admitted the interior minister, Rogelio Frigerio. A chastened president installed a solar-powered hot-water tank on the roof of the Quinta de Olivos, his official residence. “I am on a campaign to save energy,” he joked during a visit to Casa Rosada by the Mexican president, Enrique Peña Nieto. “If you’re cold, now you know why.” On June 7th the government said it would cap the rise in gas prices and increase the amount of electricity sold at concessionary rates to small consumers in some provinces.

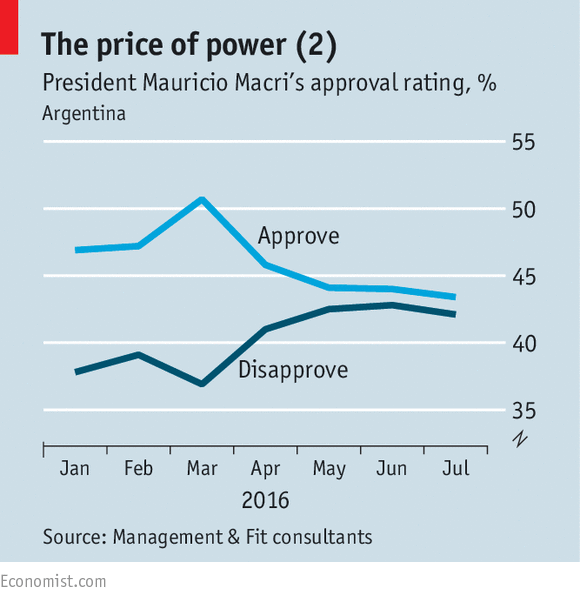

Mr Macri has reservoirs of political strength and popular goodwill to draw on. Though Argentines are angry, most still blame the Kirchners for their hardship. Allegations of corruption have enfeebled Ms Fernández as a political force. A new generation of politicians is competing to become the next presidential candidate of her Peronist party, weakening its ability to provide opposition to the government.

But Mr Macri’s honeymoon is coming to an end (see chart). With legislative elections due in October 2017, “the government needs to show some economic results in the first quarter of next year,” argues Juan Cruz Díaz of Cefeidas Group, an advisory firm. The IMF thinks the economy will rebound in 2017; it forecasts growth of 2.8%.

The row over tariffs could slow the recovery. The courts’ injunction against the price increase has shaken foreign investors’ confidence in the legal system. No one is sure whether the supreme court will reverse it. Two of its five judges were recently appointed (by Mr Macri), which makes the decision hard to predict, says Mr Díaz. Until it acts, firms will continue to face the threat of output-disrupting power cuts.

Mr Macri has little choice but to hope that the supreme court rules in his favour, persist with price rises and pay the political cost. “To find tariffs both attractive enough for investment and acceptable to society—without impacting inflation—is impossible in the short term,” says Carlos Marcelo Belloni of IAE Business School in Buenos Aires. Like chilly consumers, Mr Macri is waiting for balmier weather.

No comments:

Post a Comment