Less gold for the oldReducing Brazil’s pension burden

The president has a chance to pass a reform that will stop Brazil going bust

THE faded modernist façades along Copacabana’s beachfront hark back to Brazil’s optimistic past. The seaside promenade, where walking sticks outnumber G-strings, offers a glimpse of its demographic future. A quarter of the inhabitants of this part of Rio de Janeiro are 65 or older, making it one of the oldest places in Brazil. But the rest of the country is catching up fast, thanks to a drop in birth rates and rising life expectancy. Over-65s, who make up 8.5% of the population now, will reach Copacabana’s share by 2050. The country is dangerously unprepared for that shock.

To see why, visit the Copacabana branch of the National Institute of Social Security (INSS), which administers state pensions for Brazilians employed in the private sector. Elizete Ribeiro, a vivacious masseuse, does not look ready to be pensioned off. She is just 56 years old. But, having paid into the system for 30 years, she is entitled to a basic pension worth the minimum wage (937 reais, or $304, a month). The lawyer helping her, Jorge Freire, benefits from a separate public-sector scheme. He retired as an employee of Rio de Janeiro’s state court system when he was 52. His retirement cheque, at first the same as his final salary, is bumped up every time current court workers get a pay rise.

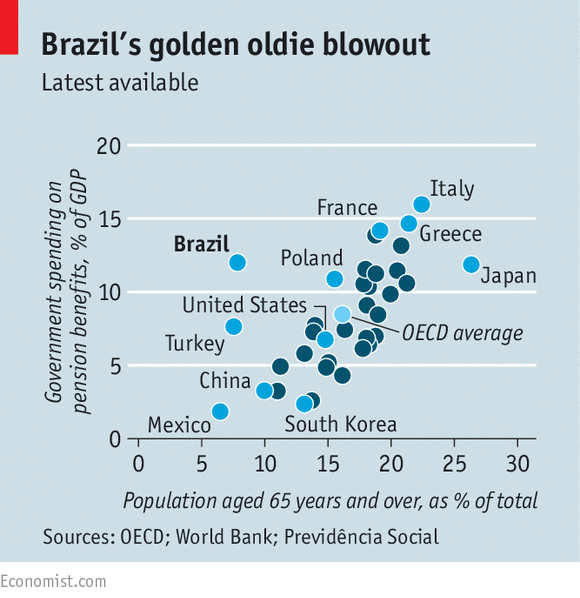

The form-filling at the INSS outpost, repeated millions of times, means trouble for Brazil. Pension spending is already the equivalent of 12% of GDP, half as much again as the average among members of the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries that have many more senior citizens (see chart). The combined annual shortfall of the pension schemes is 4.8% of GDP, equivalent to more than half the government budget deficit. The state of Rio supports more public-sector pensioners than working civil servants; for every police colonel on active duty five are retired. The state is nearly bankrupt. Without corrective action, Brazil faces an equally bleak future.

Michel Temer, the country’s centre-right president, hopes to arrange for a brighter one. He took office last year after the impeachment of his left-wing predecessor, Dilma Rousseff, and in the midst of the country’s worst recession on record. This month congress began debating his plan to reform the pension system. Economic recovery and Brazil’s financial stability depend on its success.

Brazil’s geriatric generosity came from laudable impulses. The constitution adopted in 1988 sought to break away from the country’s history of elitism and inequality, further entrenched under two decades of military dictatorship. Among the new rights was a basic pension for men over 65 and women over 60, whether or not they paid into the system. People who do pay in, like Ms Ribeiro, can claim benefits earlier. The government linked benefits to the minimum wage, ensuring that they would almost always go up and never down.

This has made Brazil a land of youthful and prosperous pensioners. Its citizens collect pensions when they are 58 on average; Mexicans toil into their 70s. Brazilians on average incomes get pensions worth four-fifths of their pre-retirement earnings, which is generous by most countries’ standards. Widows and widowers inherit the full pensions of their deceased spouses, which they can combine with their own.

This accumulation of rights has become an economic cluster bomb. Inflated by big increases in the minimum wage, pensions now account for more than half of the government’s non-interest spending. The recession has brought down the revenues to pay for them. Without a change, government pension spending could reach a fifth of GDP by 2060. Public debt will jump to scary levels sooner: by 2019 it could be 98% of GDP, up from 70% now. That prospect is one reason for Brazil’s double-digit interest rates. The pension splurge hurts the economy in other ways, for example by withdrawing employees prematurely from the workforce and taking money away from education and infrastructure.

The reform Mr Temer is proposing would reduce the pension problem to more normal proportions. It would set a minimum pensionable age of 65 years for men and women, and oblige them to work longer than they do now in order to claim the maximum allowable pension. Future rises in the retirement age to keep up with longer lives would not require amending the constitution. Only the lowest pensions would be linked to the minimum wage. Widows’ benefits would be reduced.

These and other measures would stabilise pension spending at around current levels, says Paulo Tafner, a pensions analyst. They would give the economy a short-term boost, in part by encouraging the central bank to reduce interest rates more rapidly. The stockmarket has strengthened on hopes that congress will enact it.

Because the reform requires a constitutional amendment, both houses must pass it with three-fifths majorities. Ms Rousseff’s Workers’ Party decries it as an attack on the poor, though it will not touch beneficiaries of the lowest pensions. A politician from Mr Temer’s coalition accuses the government of “demographic scaremongering”—as if ageing were unpredictable.

Despite such grumbling, Mr Temer has a good chance of getting the reform through reasonably intact. A poll for his Party of the Brazilian Democratic Movement reportedly shows that Brazilians are split evenly for and against the reform. The government is trying to tip the balance, with adverts in newspapers and videos beamed at passengers in airports. Mr Temer himself is unpopular. But if he cleans up the pension system, Brazilians will have reason to thank him.

No comments:

Post a Comment