How to Become an International Gold Smuggler

Harold Vilches, a 23-year-old Chilean, exported $80 million in contraband gold. It all started with a Google search.

Photographer: Tomas Munita for Bloomberg Businessweek

As the minutes ticked by on the afternoon of April 28, 2015, Harold Vilches watched stoically while customs officers at Santiago’s international airport scrutinized his carry-on. Inside the roller bag was 44 pounds of solid gold, worth almost $800,000, and all the baby-faced, 21-year-old college student wanted was clearance to get on a red-eye to Miami. Vilches had arrived at the airport six hours early because he thought there might be some trouble—he’d heard that customs had recently seized shipments from competing smugglers. But Vilches had done this run, or sent people to do it, more than a dozen times, and he’d prepared his falsified export paperwork with extra care. He was pretty sure he wouldn’t have any trouble. While he waited, he texted his contacts in Florida, telling them he’d already cleared customs.

The plan was to hand off the gold at the Miami airport to a pair of guards, who would load it into an armored truck for the short trip to NTR Metals Miami LLC, a company that buys gold in quantities large and small and sells it into the global supply chain. The modesty of its shabby office, where a receptionist sits behind an inch-thick acrylic barrier, belies the amount of business that goes on inside. U.S. Department of Justice investigators believe NTR Metals Miami has bought at least $3 billion in South American gold in the past four years, much of it from illegal mining operations, people familiar with the investigation say.

Vilches didn’t need this headache. In just two years he had rapidly risen in the ranks of Latin American gold smugglers. Although he was barely old enough to order a beer in Miami, he’d won a $101 million contract to supply a gold dealer in Dubai. That hadn’t exactly worked out—the Dubai company was after him for $5.2 million it says he misappropriated—but still, in a brief career he’d acquired and then resold more than 4,000 lb. of gold, according to Chilean prosecutors. U.S. investigators and Chilean prosecutors suspect almost all of it was contraband.

That evening at the airport, Vilches employed his standard cover story, saying that the gold came from coins acquired from customers and recast as ingots. The customs officers weren’t buying it. The laboratory Vilches had used to vouch for the gold wasn’t government-certified, they said, and they doubted his claims that the gold had come from coins. Vilches was irate. He couldn’t believe it when the man behind the desk called his boss and then relayed orders from above: If it’s Vilches’s gold, seize it.

Investigators with the Policía de Investigaciones, Chile’s equivalent of the FBI, had been monitoring Vilches for months, intercepting his phone calls and scouring the export papers he’d submitted. The kid was clever, they agreed, but who was he working for? “I thought there was someone behind him, always,” says José Luis Pérez, a Chilean prosecutor on the case.

After the airport officials confiscated Vilches’s gold, they let him go. For the next 15 months, Chilean authorities allowed Vilches to bring illegal gold in and ship it out as they built a case, searching for associates and those above him. They listened in on various telephones, read Vilches’s text messages, and followed couriers. They watched as smugglers brought gold south from Peru, across remote stretches of desert and through valleys in the Andes Mountains, or west from Argentina, driving over the snowy mountain pass in the shadow of 22,800-foot-high Aconcagua, then down to Santiago and Vilches’s headquarters, a place police nicknamed “The Bunker.” Inside, Vilches assayed, weighed, and paid for the gold. He melted it down and recast it as ingots, then flew it, or used a family member to fly it, to Miami.

An illegal mine in Peru. The primary tools in this type of mining are fire hoses and mercury.

Photographer: Tomas Munita/The New York Times/Redux

To their growing amazement, the police never found the larger organization they presumed was supporting and protecting Vilches. There was, as far as they could determine, no bigger fish. Finally, in August 2016, they arrested him. Investigators say they have documented $80 million in gold shipments that moved through his hands via eight shell companies he established in Chile and Miami—and they think there was much more. They charged Vilches and four associates, including his wife and her father, with racketeering, smuggling, customs fraud, and money laundering. None of them have been tried, and the case remains open. Vilches’s wife and father-in-law declined through their lawyer to comment. Today, Vilches lives with his wife in an apartment in a rundown part of Santiago; he’s under house arrest from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m.

In exchange for his release from jail, Vilches provided extensive testimony that has allowed Chilean prosecutors and the U.S. Department of Justice to try to build a huge, multinational gold smuggling case. Interviews with police and prosecutors in Chile and the U.S. and hundreds of pages of police files describe Vilches’s part in a black market that adds literally tons of illegally mined and contraband gold to the international economy every year.

In the past decade and a half, global gold consumption has risen by almost 1,000 tons a year, to about 4,300 tons, according to the World Gold Council, a London-based industry group. Legal mining operations haven’t kept up with demand, so illegal mines controlled by criminal gangs, from the Amazon to central Africa, help cover the deficit, according to Verité, a nonprofit group in Amherst, Mass., that’s researched the illegal gold trade. A 2016 Verité study found that five countries in Latin America shipped 40 tons of gold from illegal mines to the U.S. in one year, almost twice the legal exports from those countries. South America’s illegal gold mines, most of them in the Amazon basin, are toxic pits in which mobs of laborers use fire hoses and mercury to extract nearly pure gold nuggets from the red earth. According to a finding by the United Nations, the industry thrives on child labor, devastates the environment, and enables prostitution at ramshackle camps around the mines. The gold moves from smuggler to smuggler, then into a network of refiners and traders, all feeding the world’s voracious demand.

Vilches, a city kid, never saw any of this, but he did grow up around gold. His father, Mario, owns a jewelry shop; his uncle Enrique, an evangelical preacher, built Joyas Barón, a chain of 18 jewelry stores. Enrique has more than once attracted the attention of the authorities. In 1998, Chilean prosecutors caught Ecuadorean smugglers with 18 ingots of gold at the airport, and they claimed to be delivering it to Enrique. (He was cleared of all criminal charges after arguing that police set him up.) In March 2015, Enrique was sentenced to five years’ probation for tax fraud by an appeals court in Santiago. Last year tax authorities filed further charges alleging that Enrique had organized an enormous accounting scam and owed an estimated $18 million in back taxes. Speaking on Chilean TV, Enrique Vilches denied all connections to his nephew’s gold smuggling. “I don’t have any commercial relationship with what’s being investigated,” he said. “[There’s] no situation that involves me, therefore I want to remain absolutely separated from this situation.”

By 15, Harold was working for his father’s business. Within a year, his dad was stuffing his backpack with up to 50 million pesos ($78,000) in cash and sending him to the bank to make deposits. In 2013, Vilches entered college at the Universidad Mayor in Santiago to study business administration. He hadn’t been there long when his father had a stroke, and he cut back his classwork to focus on the family business. If he was going to be doing that, he decided, he wanted to do more than buy and sell trinkets. He intended to make some real money, and that meant getting into the bulk gold business.

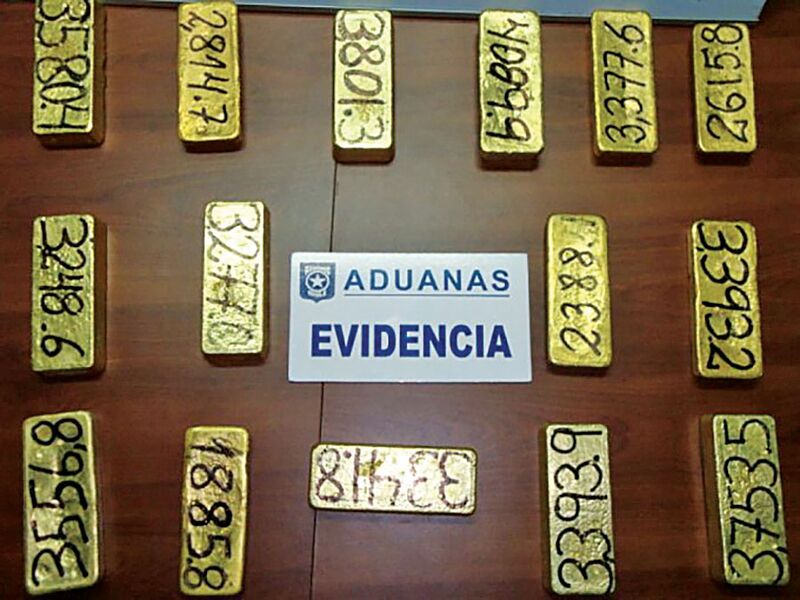

Gold seized in 2014 from Vilches’s couriers. They were trying to bring 48 kilos to Santiago.

Source: National Customs Office Chile

His first move was to persuade Gonzalo Farias, a metals exporter in Santiago, to take him on as a supplier. In September 2013, Vilches made his first delivery to Farias—6.6 lb. of gold legally acquired in Chile. He made several more such deliveries. But he wanted to be bigger. He went around Farias and cut a deal directly with Fujairah Gold, a Dubai-based company that Farias supplied. In June 2014, Vilches signed a contract to deliver 6,000 lb. of gold over the next 12 months to Fujairah’s head office. The contract began with 90 lb. the first month, then ratcheted up. He didn’t have the money to buy that much gold, so the company gave him access to an account holding $5.2 million. This was his big break—the contract was potentially worth more than $100 million. He stood to make $2 million to $6 million in profit.

This was beyond ambitious for Vilches—there weren’t enough available gold coins and jewelry in Chile to fill Fujairah’s orders. So Vilches decided to become a smuggler. It was easy: He Googled gold dealers in Peru. He found Rodolfo Soria Cipriano, one of the country’s most prolific exporters, according to Peruvian newspaper El Comercial. An answer came quickly. Vilches told investigators Soria promised to set him up with all the gold he wanted if he showed up with the cash. Vilches said he didn’t ask where the gold came from. Whatever its source, he evaded export controls and moved the gold into Chile without paying taxes or duties, prosecutors say.

Soria made introductions to a network of suppliers, with whom Vilches later arranged buys via WhatsApp messages. Once the gold was ready for pickup, he would fly to Arica, in northern Chile, where he kept a Mazda sedan expressly for trips into Peru. On at least 10 trips, beginning in the middle of 2014, Vilches says, he and his father-in-law drove across the border to the city of Tacna, a few miles inside Peru, with the door panels of their car stuffed with cash, as much as $2 million at a time.

Vilches bragged to prosecutors that he moved with ease in the criminal world. With relish, he described making a buy at a safe house in Tacna. While his father-in-law waited outside in the car, Vilches was escorted by armed men through multiple metal detectors and locked gates before arriving at a secure room that held a huge stash of gold. He suspected the house doubled as a cocaine dealing operation, he told prosecutors, but he kept his cool. He tested the gold for purity, then went back outside, packed the contraband into the door panels of the Mazda, and drove back to Chile.

Mining at a government-designated site in the indigenous San Jacinto community in the Madre de Dios region of Peru.

Photographer: Tomas Munita/The New York Times/Redux

Vilches began making as many as five gold runs a month to Peru and also hired couriers, who delivered to him directly in Santiago. It added up to enough to allow him to make several successful deliveries to Fujairah using air cargo companies. Then, in August 2014, customs agents at the airport in Arica stopped a pair of his couriers with 105 lb. of gold. The paperwork and the duo’s explanations about how they’d obtained the gold didn’t add up. The gold was seized, and Vilches was looking at his first legal trouble: a tax-evasion case, which has yet to be resolved.

Vilches decided to abandon Fujairah. Fulfilling the contract would require dozens of buying trips or courier runs, and getting the gold to Dubai would involve massive logistical challenges. When the company asked about its overdue deliveries, Vilches invented excuses. But lawyers for Fujairah were convinced he was lying. They suspected he was selling to other companies on the side. Fujairah also came to the conclusion that the gold was illegal.

Almost two years later, Vilches faced his first criminal charges, for fraud and appropriating $5.2 million from Fujairah Gold. Through his lawyer, Marko Magdic, Vilches denied the charges and said the only issue was a breach of contract. Fujairah continues to press claims in court to recover the money.

As his relationship with Fujairah deteriorated, Vilches sought new buyers. He knew some of his Chilean clients were selling the gold he brought from Peru to NTR Metals in Miami. Soria, he told prosecutors, made an introduction. “I was cleared by the company’s compliance committee in more or less three weeks,” he told the FBI. Trey Gum, general counsel for Elemetal LLC, NTR’s parent company, says the company established a relationship with Vilches only after its representatives visited his companies in Chile. “The information NTR Miami received was that Mr. Vilches came from a family of established jewelers with close ties to the evangelical community in Chile,” Gum said in an emailed statement. Soria couldn’t be reached for comment. The offices of his company in Lima appear to have shut down, and its phone numbers are out of service.

Vilches told prosecutors he then went to Florida and met with two NTR executives: Renato Rodriguez, executive sales director for Latin America, and Samer Barrage, who oversees the Miami operation. They sat down together at a restaurant in Coral Gables. “They knew something was up with my gold because it was so pure. ... A few months later I expressly told them it was contraband gold,” Vilches said. He also told prosecutors that Rodriguez and Barrage coached him on falsifying customs paperwork.

None of this is true, according to Rodriguez and Barrage. Standing in the lobby of NTR’s Miami office, Rodriguez says the company trusted the documentation Vilches provided—as did, he points out, customs officials in Chile and the U.S. “All that stuff is made up,” he said. Barrage said in an email: “I want to be emphatically clear at no point did I have any knowledge whatsoever regarding his metal being sourced from illegal mining operations. There was absolutely no coaching or involvement regarding his export process or import process for that matter.”

To maximize the appearance of legitimacy, Vilches wanted to cast his gold into brick-size ingots, with a seal identifying the weight and purity. It was a challenge—he’d watched his father do it, but he had almost no idea how to manage it himself. When he plugged in an imported machine to melt the gold, it shorted out and filled his office with black smoke; he’d neglected to buy a transformer so the equipment would work with Chile’s higher-voltage electrical system. Eventually, Vilches says, he and his father-in-law taught themselves how to make the ingots by watching YouTube videos.

In December 2014, Vilches made his first delivery to NTR Metals Miami, with a suitcase full of gold bars. That was how he capped his first full year in business, during which he shipped 3,119 lb. of gold valued at $57.4 million, export records cited in the criminal investigation show. Chilean investigators later cited 10 shipments from Vilches to NTR as clearly illegal because of falsifications in customs declarations and failure to pay taxes and duties on the initial importation of the gold.

Chilean prosecutors say they have evidence NTR was aware the gold was illegal or contraband based on Vilches’s statements and his telephone, email, and text communications, all of which they’ve shared with U.S. investigators. “NTR knows the gold is illegal. It’s cheaper than legitimate gold. That’s the business,” says Tufit Bufadel, a Chilean prosecutor involved in the case.

In early 2015, Vilches told the FBI, Rodriguez and Barrage summoned him to Miami to make a bold proposal. “They asked me to find a gold supplier in Africa,” he said. According to Vilches, the NTR executives proposed that he try to arrange a 1,000-kilo-per-month smuggling operation.

Vilches was game. If he could pull it off, he’d be moving an estimated $20 million a month in dirty gold. But it was going to be complicated. “What they told me is that, because of compliance policies, they could not receive African gold,” Vilches told the FBI. “So they proposed that I export from Africa to Chile and then send it to Miami to NTR Metals.”

Vilches flew to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, where he spent almost a month viewing stashes of gold and negotiating with South African and Cameroon-based traders. He told the FBI he “maintained constant communications with Renato and Samer” about possible shipping routes. But he got scammed out of $300,000 by someone he thought was a supplier. The entire Tanzania affair unnerved him. At one point, he told the FBI, he was accosted by two carloads of armed men—probably government security forces, he thought—and held for hours in a grimy room while being interrogated about his business in Tanzania. He was relieved to escape with his life.

Rodriguez and Barrage denied suggesting Vilches go to Africa. “In fact, in 2015 he asked if we purchased from Africa,” Rodriguez wrote in an email. “I unequivocally told him no and that it was a policy of NTR not to do so.” Barrage wrote: “There was ... no encouragement to source gold from Africa.”

The bunker where Vilches processed gold and dummied up paperwork.

Photographer: Tomas Munita for Bloomberg Businessweek

Despite the setbacks in Tanzania, Vilches had a good 2015. He spent his money on a $1 million home adjacent to a lake with lilies and swans. He also invested $150,000 in a fortified building in Recoleta, a Santiago neighborhood where stray dogs roam streets strewn with trash. Graffiti-covered 12-foot walls topped with barbed wire surrounded a two-story building outfitted with Level 5 bulletproof glass and armored metal doors. Steel-reinforced walls and an array of 32 security cameras protected an inner sanctum. The final touch was a pepper spray system. “Even in a bank you don’t see such high-quality protection and security measures,” says Pérez, the Chilean prosecutor.

It was here that Vilches toiled, usually alone, transforming his gold into the standard-size ingots needed to avoid raising suspicions at customs. He marked each with the precise weight and purity and added the seal of Aurum Metals LLC, a company he’d set up in Miami. It was also in the bunker that Vilches stashed cash and falsified documentation for the gold.

Vilches told prosecutors that the NTR executives advised him to make videos of the refining process to better support his claims that the gold came from legal sources. He did that, and his marketing brochures carried photos of himself grinning while pouring liquid from a flask like a high school chemistry student, except that the flask was filled with liquid gold.

NTR Metals Miami is one of the 49 offices of NTR Metals, also known as Elemetal Direct, one of eight divisions of Dallas-based Elemetal LLC. Elemetal Direct sells its gold as 99.99 percent pure bullion—and certified as coming from legal mines by industry groups. Those groups include the London Bullion Market Association, or LBMA, the industry’s self-regulating body, which counts officials from major banks and gold traders on its board. Elemetal dedicates a section of its website to certifications of quality and origin, including a copy of the LBMA’s “responsible gold certificate” from a “third-party audit of the company’s supply chain due diligence.” LBMA spokesman Aelred Connelly declined to comment about Elemetal’s certification.

Another certificate comes from the Conflict-Free Sourcing Initiative of the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition, or EICC. It’s for Elemetal’s gold smelter in Jackson, Ohio. To renew the certification each year, Elemetal hires auditors to review purchase and import records, tour the smelter, and interview employees about the source of purchased gold. The mission is to assure that no gold comes from illegal mines that give rise to prostitution, labor abuses, and environmental damage or fund illegal activities or war, especially in Latin America, says Leah Butler, director of the conflict-free smelter program at the EICC. “We know that gold from Latin America is high-risk,” says Butler. She declined to comment on Elemetal, citing EICC rules. The organization “takes allegations of wrongdoing by any smelter or refiner in its program very seriously,” she says.

Amjad Rihan, a former Ernst & Young auditor who specializes in researching commodity supply chains, says it’s easy to fool auditors. Rihan now works for Martello Risk, a London consulting firm that helps companies scour supply lines for illegal minerals. “The problem is these audits really don’t go beyond the paperwork,” he says.

These seals of approval are critical across the industry. Under U.S. and European law, corporations must ensure their suppliers aren’t buying from mines that fund conflict. So they source gold from companies that are certified as having clean supply chains. Elemetal’s certified smelter is a valuable asset that allowed the company to supply 68 Fortune 500 companies in 2015 according to a Verité analysis of corporate conflict minerals reports, which are required under the U.S. Dodd-Frank Act. Those include Alphabet, Apple, GE, GM, and HP, the latest corporate filings show.

According to Gum, Elemetal’s lawyer, NTR Metals Miami stopped doing business with Vilches on June 1, 2016, the day the fraud charge against him was filed, and “reported the matter to appropriate governmental authorities.” Elemetal also, “as a precautionary measure,” ordered NTR Metals Miami to “suspend all operations in Chile pending a review of current risks and procedures in that country,” Gum says.

On the night everything began to fall apart, when agents at the Santiago airport seized the five ingots in his carry-on, Vilches immediately called NTR, he told FBI investigators. Rodriguez and Barrage suggested, he said, that he forget about ever seeing that gold again and concentrate on getting the paperwork right the next time. NTR executives “gave me instructions to keep U.S. Customs from realizing my certificates of origin were false,” Vilches said.

It seemed to work, for quite a while. Chilean police were itching to bust him, but prosecutors ordered detectives to stand down to gather more evidence. They were reluctant to give up on the idea of snagging someone higher than Vilches. And so he both imported and exported dirty gold without interruption.

The net began to close in early 2016, when banks in Chile and Miami began filing suspicious-activity reports on Vilches’s huge cash transactions and shutting down his accounts. Then came the criminal complaint involving the Fujairah Gold contract. Finally, police arrested Vilches and seized $300,000 in cash and a small amount of gold from the bunker. Facing a multiyear jail sentence for money laundering and tax evasion, Vilches agreed to cooperate with law enforcement in both the U.S. and Chile. He also dropped out of college. Today, Vilches and NTR Metals are at the center of a sweeping criminal investigation by the U.S. Justice Department, Chile’s National Economic Prosecutor’s office, and law enforcement in Peru and Ecuador, according to Pérez, the Chilean prosecutor. Sarah Schall, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Miami, declined to comment, citing policy against confirming or denying the existence of an investigation.

In October 2016, FBI agents and prosecutors with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Miami traveled to Chile to interview Vilches. After becoming convinced his information was legitimate, they told him he might get immunity in the U.S. from prosecution in exchange for his sworn testimony, people with knowledge of the probe say. As Vilches spent hour after hour in interrogation, FBI agents and Chilean detectives were both fascinated and entertained. Upwards of 15 law enforcement professionals crowded into a meeting room at Santiago 1, a sprawling prison complex, and Vilches fed off the attention. He laughed and seemed to shrug off the seriousness of his situation. His confessions took on the air of a performance, according to one of the investigators present. “All you lacked was the popcorn,” he says with a laugh. FBI agent Lourdes McLoughlin, the assistant legal attaché at the U.S. embassy in Santiago, declined to comment, citing a policy of not commenting on active investigations.

In December the U.S. Attorney’s Office and FBI brought Vilches to Miami, where he told a federal grand jury that he was coached by NTR Metals Miami on how to set up his corporate structure in the U.S. to handle smuggled gold and then launder the proceeds, people familiar with the U.S. probe say. Elemetal and NTR Metals Miami didn’t respond to questions about an investigation.

Vilches lived large only briefly. He’s traded down to an apartment along Gran Avenida, a thoroughfare in a tough Santiago neighborhood. Because of his cooperation, he’s unlikely to face additional jail time for smuggling. He still faces multiple criminal charges, including tax evasion.

Chilean export regulations have been beefed up in the wake of the Vilches case. One gold dealer describes the new export process as similar to “being told to stand up against the wall and put your hands up.” Customs officials from Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru have visited Chile to exchange information and compare notes. Pérez approves, but he has no illusions. If Vilches, without any particular advantages except his boldness, could get this far in the illegal gold trade, who else could? “I think there are 100 Vilcheses across Latin America,” he says. “It’s easier than it looks.”

—With assistance from Ben Bartenstein

Inside Amazon’s Battle to Break Into the $800 Billion Grocery Market

After almost a decade of food retail experiments with little success online, the e-commerce giant is embracing the physical stores it once shunned.

The new Amazon Go grocery store in Seattle is adjacent to Amazon’s headquarters.

Photographer: David Ryder/Bloomberg

“Very wasteful” isn’t a phrase usually associated with Amazon.com Inc., which is so cost-conscious it once removed the light bulbs from its cafeteria’s vending machines. But after spending several months analyzing the online retailer’s grocery-shipping hubs back in 2014, that’s exactly how a mechanical engineering student described its approach to selling bananas.

Workers at Amazon Fresh, the company’s grocery-delivery business, threw away about a third of the bananas it purchased because the service only sold the fruit in bunches of five, the student concluded. Employees trimmed each bunch down to size and chucked the excess.

The research paper by Vrajesh Modi, who now works for Boston Consulting Group, highlighted other problems: Poorly trained employees often stood around with nothing to do. Moldy strawberries were frequently returned by disappointed customers. Amazon’s inspectors believed their corporate bosses didn’t care much about the quality of the food.

Such challenges linger for Amazon. Despite several attempts to break into the $800 billion grocery industry and almost a decade in the business, the company has struggled to entice shoppers en masse to buy eggs, steaks and berries online the same way they’ve flocked to buy books, tablets and toys.

“Online grocery is failing,” said Kurt Jetta, chief executive officer of TABS Analytics, a consumer products research firm. Only 4.5 percent of shoppers made frequent online grocery purchases in 2016, up just slightly from 4.2 percent four years earlier despite big investments from companies such as Amazon, according to the firm’s annual surveys. “There’s just not a lot of demand there. The whole premise is that you’re saving people a trip to the store, but people actually like going to the store to buy groceries.”

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos now seems to understand that he can’t win the grocery game with websites, warehouses and trucks alone. The world’s biggest online retailer sees brick-and-mortar stores playing a key role in a renewed grocery push, documents reviewed by Bloomberg show. And like it did with Amazon Fresh, the company is launching its newest projects in Seattle, its home town.

Last Tuesday, men in cherry pickers worked through driving rain to affix “Amazon Fresh” signs to a drive-in grocery location in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, where shoppers can stop and have online orders loaded into their cars. Crews were busy on a similar site south of downtown, readying canopies over parking spaces to protect customers from the elements as they pick up their shopping bags. The secretive company has yet to announce the projects, and crews have covered the Amazon signs in black fabric and paper.

Late last year, Amazon purchased supply-chain software from LLamasoft Inc.– a major departure for a company known for its logistics prowess, and defying an internal mantra of “we don’t buy, we build.” And it more recently restructured how various grocery teams were managed to narrow their focus and set clear priorities, according to people familiar with the company’s business.

These changes come as Amazon breaks from its standard formula of shipping products in boxes out of jam-packed warehouses. Instead, it will invite shoppers inside its own grocery stores to smell the oranges, see the tomatoes and tap the watermelons. Ahead of a national rollout next year, Amazon is testing three brick-and-mortar grocery formats in Seattle — convenience stores called Amazon Go, the drive-in grocery kiosks, and a hybrid supermarket that mixes the best of online and in-store shopping. The company may open as many as 2,000 stores, according to internal documents.

Workers clean up at one of Amazon’s new drive-through grocery pick-up locations.

Photographer: David Ryder/Bloomberg

The company has said little about its grocery-store plans, aside from a video about Amazon Go’s no-checkout format that has racked up more than 8.7 million views on YouTube. An Amazon spokeswoman declined to comment for this story. Reports on its moves have dribbled out over the past several months, prompting occasional denials and retorts from the company. Seattle technology site Geekwire in August uncovered Amazon’s mysterious drive-in grocery kiosk in Ballard. The New York Post in February said Amazon aimed to create “robot-run supermarkets” that would operate with only a few people. Bezos responded by tweeting to the Post: “Whoever your anonymous sources are on this story — they’ve mixed up their meds!”

Amazon’s goal is to become a Top 5 grocery retailer by 2025, according to a person familiar with the matter. That would require more than $30 billion in annual food and beverage spending through its sites, up from $8.7 billion — including Amazon Fresh and all other food and drink sales — in 2016, according to Cowen & Co.

Reaching that milestone would require a new wave of store and warehouse investments around the country, costing billions of dollars. That’s an existential change for Amazon, which initially stayed away from perishable goods and has mostly avoided the overhead of physical stores since it started in 1994.

Photographer: David Ryder/Bloomberg

“A bunch of smart people at Amazon have been thinking about re-imagining the next phase of physical retail,” said Scott Jacobson, a former Amazon executive who is now a managing director at Madrona Venture Group. “They want more share of the wallet, and habitual, frequent use of Amazon for groceries is the ultimate goal.”

For Amazon shoppers interested in buying groceries online, the company’s current offerings can be confusing. Amazon Fresh is available in about 20 U.S. cities for those paying $14.99 a month. Amazon Pantry lets shoppers buy crackers, cookies, chips, coffee and other non-perishables for a delivery fee of $5.99 per box. Amazon’s speedy drop-off service, Prime Now, offers items from local grocers in some cities, but no major chains. Its stick-on Dash Buttons let people order many household products — including some groceries, but not fresh food — with a finger tap. And Subscribe & Save offers discounts to Amazon customers who sign up for periodic delivery of laundry detergent, toothpaste, diapers, paper towels and other items frequently purchased in grocery stores.

The various initiatives have been a source of increasing internal tension as employees on different projects compete to sell the same things, according to a person familiar with the matter.

One problem saddling Amazon Fresh is the high cost of losses caused by food going bad, an issue it’s never faced with books and toys. For conventional grocery sellers, browning bananas can be sold at a discount to smoothie-makers and bread bakers. Chicken breasts nearing their expiration dates can be marked down. With Amazon Fresh, such items must be discarded or are returned by frustrated customers, according to a person familiar with the matter. That has meant Amazon Fresh has lost money from spoilage at more than double the rate for a typical supermarket, said the person, who asked not to be identified discussing internal operations. The main reason Amazon began delivering groceries through Prime Now was to hand that risk back to the local grocers to lower Amazon’s costs. The company didn’t originally anticipate the scope or difficulty of these problems because so few people working on its grocery push have experience in the industry.

“Grocery is the most alluring and treacherous category,” said Nadia Shouraboura, a former Amazon executive whose company, Hointer, has been working on redefining in-store grocery shopping for the past 18 months. “It lures inventors and retailers with shopping volume and frequency, and then sinks them with low margin.”

Beyond grocery, Amazon executives have also discussed opening consumer electronics stores to showcase its gadgets and better compete with Best Buy Co., according to three people familiar with the plan. For years, Amazon executives have discussed the downside of an online-only strategy, mostly with regard to a lack of places for shoppers to try out Kindle electronic readers, the voice-activated Echo speaker and its defunct Fire smartphone. Amazon considered holding events similar to Tupperware parties when it introduced its first Kindle in 2007, fearing the products would languish unseen, Jacobson said. The handful of bookstores Amazon has opened around the country double as gadget showrooms, similar to the Apple Store.

Long term, a stronger grocery business could position Amazon to become a wholesale food-distribution business serving supermarkets, convenience stores, restaurants, hotels, hospitals and schools. But first the company has to find a way to get more people to think of Amazon when stocking their refrigerators and pantries.

Photographer: David Ryder/Bloomberg

A group of Amazon executives met late last year to discuss the disadvantage Amazon faced compared with grocery competitors such as Wal-Mart and Kroger because of its lack of physical stores and customer apprehension about buying fresh foods online. They decided they needed something more to jump-start Amazon’s grocery push beyond plans already under way for the Amazon Go convenience store, modeled for urban areas, and drive-in grocery pick-up stations suited for the suburbs.

They worked out plans for a third approach: grocery stores closer in size to a Trader Joe’s than a Wal-Mart to offer easy access to milk, eggs and produce. Other items like paper towels, cereal, canned goods and dish detergent would be stocked on-site in a warehouse where they could be easily packed and delivered to shoppers at the location, according to documents reviewed by Bloomberg. It would also serve as a delivery hub for online orders.

Brittain Ladd, a supply chain consultant who joined Amazon in 2015 and most recently worked on its Amazon Fresh and Pantry expansions, wrote about such a store prior to joining Amazon in an academic paper called “A Beautiful Way to Save Woolworths.”

Ladd envisioned two-story buildings where shoppers browse produce, bread and other fresh items on the ground level while their orders for paper towels, canned goods and cereal are packed in a warehouse above. “The stores will have the capability to fulfill online orders placed by customers within a specific radius of the store,” he wrote. “Amazon drivers and/or contractors will be assigned to deliver groceries.”

The executives decided such a store would be worth pursuing for Amazon Fresh and ordered further research about ideal locations, how to integrate the stores with grocery delivery, and the use of automation to reduce overhead. Site selection for this store’s first model is happening now in Seattle, according to a person familiar with the plan.

Meanwhile, the first wave of its new grocery experiment, Amazon Go, was unveiled in December and for now is only open to employees while the systems are tested. Cameras and sensors monitor shoppers who scan their smartphones upon entering, allowing them to grab items like sandwiches, yogurt, drinks and snacks and automatically pay for them without a checkout kiosk. Products are embedded with tracking devices that pair with customers’ phones to charge their accounts. Weight-sensitive shelves tell Amazon when to restock. A patent filed by Amazon in 2014 suggests it could use facial-recognition technology to identify and then automatically charge in-store shoppers.

In its video touting Amazon Go, the company said it was aiming to open the site to the public in “early 2017,” and it hasn’t provided an update to that timing. But the technology has been crashing in tests when the store gets too crowded and requires human quality control, people watching video images to make sure customers are charged for the right things, according to a person familiar with the plan.

Beyond letting customers skip lines, the technology gives Amazon valuable data, said Guru Hariharan, founder of Boomerang Commerce Inc., which designs software for large retailers. Even if customers don’t purchase everything they touch, there’s value in understanding what shoppers consider but don’t ultimately buy, he said. That makes it worthwhile for Amazon to work through the kinks in the technology.

“It takes a lot of time and experimentation to work through unpredictable scenarios like a child picking up an item or a person wearing sunglasses or a face muffler,” he said.

At the same time, recent work and construction permits indicate the new drive-in grocery kiosk in Ballard could open any day.

“Amazon wants to be the first thing any consumer thinks of when they need to buy anything,” said Jim Hertel, a senior vice president at marketing technology company Inmar Inc. “Food is the largest retail category. They can’t do what they want to do without grocery and they’re definitely not going to give up.”

Photographer: David Ryder/Bloomberg

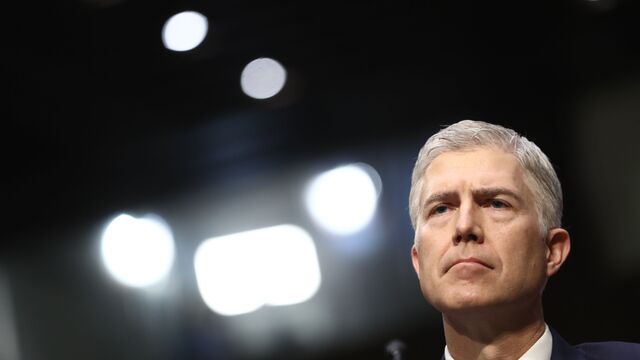

Beyond Roe v. Wade: Here’s What Gorsuch Means for Abortion

Neil Gorsuch's confirmation to the Supreme Court would reboot a 25-year campaign to chip away at abortion rights.

Illustration: Isabel Seliger/Sepia

Last year, on a presidential debate stage opposite Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump vowed, once president, to appoint “pro-life judges” to the Supreme Court. After enough of them, he said, the reversal of Roe v. Wade—the 44-year-old opinion that made abortion legal throughout the United States—would “happen automatically.”

But Roe cannot be that easily overturned—at least, not just yet. Even if Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch’s stance on abortion proves similar to that of his predecessor, Antonin Scalia, he would, if confirmed, only return the court to roughly the balance it held before Scalia’s death. The landmark ruling that advocates on both sides of the abortion debate should focus on isn’t Roe but its 1992 revision of sorts, Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Let’s back up.

In Roe v. Wade, decided in 1973, the Supreme Court found that a woman’s decision to keep or terminate a pregnancy was her own to make, in consultation with her medical provider, and was legally protected by a constitutional right to privacy. The 7-2 decision nullified laws that had criminalized abortion in 46 states, and it fueled legal and political battles that still show no sign of abating.

Most Americans’ opinions on whether abortion should be legal are not absolute. A 2016 Pew Research poll found that 58 percent believe there are situations in which abortion should be legal and situations when it shouldn’t. Only 38 percent hold absolute views, believing either that it should always be legal (23 percent) or never be legal (15 percent). This variety of opinions has been remarkably consistent over the decades. In fact, a 1972 Gallup poll taken before Roe’s decision found that 64 percent of Americans believed “decision to have an abortion should be made solely by a woman and her physician.”

Roe reflected that lack of consensus. In its majority opinion, the court noted that abortion was legal at the time of the United Sates’ founding and that most laws prohibiting abortion were relatively recent, dating to the late 19th century. Still, the court found that government did have a vested interest both in the health of the mother and the future of her unborn fetus. It decided that restrictions could not be placed on abortions performed during the first trimester of pregnancy—at that point, abortion is safer for a pregnant woman than giving birth—but could be enacted for second-trimester ones to protect her health. In the third trimester, by which point many fetuses have become viable, abortion could be restricted in the interest of the unborn, except when it was necessary to preserve the health of the woman.

After Roe, states passed abortion restrictions within this trimester-based framework. The more onerous ones led to lawsuits, culminating in the 1992 Supreme Court case Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

At issue was a Pennsylvania law that required that doctors inform patients seeking abortions of any “risks and alternatives,” that parents be notified of a minor’s abortion, that spouses be notified of a wife’s abortion. It also mandated a 24-hour waiting period between a patient’s initial medical consultation and the actual procedure.

The Supreme Court invalidated the law’s spousal-notification requirement, finding that a husband’s “interest in the fetus” doesn’t override a woman’s constitutional rights. But by a 5-4 plurality vote—various judges agreed in parts and dissented in other parts, failing to form a solid majority—it upheld all the others, finding that they did not put an “undue burden” on women. It also issued a long, impassioned explanation of why Roe should not be overturned—something that may give pause to judges set on overturning the decision in the future.

“The ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives,” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote for the plurality. Since Roe, she wrote, an entire generation of American women had formed relationships and started—or decided not to start—families under the assumption they had this right; to overturn something so momentous would call into question the court’s own legitimacy. “Roe is clearly in no jeopardy,” she wrote.

“That is why Casey is the key here,” says Julie Cantor, a Los Angeles litigation attorney and a lecturer of medical ethics and the law at UCLA School of Law. “It upholds Roe but establishes this ‘undue burden’ rule that gives you the framework for everything that came after it.”

“However—and there is a big ‘however,’” adds Carol Sanger, a professor at Columbia Law School, “the court also said, ‘We think that Roe didn’t get it right in every regard.’ And they threw out the trimester framework.’”

Casey left states free to regulate abortion throughout all stages of a pregnancy and to outlaw it completely after a fetus becomes viable, generally understood to be around 24 weeks—provided the woman’s health wasn’t in danger, and provided the regulation didn’t pose an “undue burden.”

The trouble was that Casey didn’t define “undue burden” other than as a regulation with “the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion.” It didn’t specify what constituted a substantial obstacle.

“The court really didn’t provide much guidance,” says Janet Crepps, senior counsel with the Center For Reproductive Rights. “That left district courts and courts of appeals to more or less fill in the blanks. Depending on evidentiary showings or the judicial philosophy of judges, we were getting all sorts of different results.”

Since then, states have passed dozens of such requirements, more than 60 last year alone. Many of them, including multiple-day waiting periods and mandatory ultrasounds, have held up in court. Others like Arizona’s 2012 ban on abortions performed more than 20 weeks after a women’s last menstrual period—or likely 18 weeks from conception, well before viability—have been struck down. In March, Mike Pence, then still the governor of Indiana, signed a law to require that aborted fetal remains be cremated or buried; a federal judge blocked it. Similar laws in Texas and Louisiana met the same fate.

In June, with just eight justices, the Supreme Court finally clarified its ‘undue burden’ rule when it decided Whole Woman’s Health vs. Hellerstedt. In a 5-3 vote, the court found that a Texas law requiring doctors at abortion clinics to have hospital-admitting privileges was not medically necessary—many riskier medical procedures, like colonoscopies, did not come with these requirements—and therefore posed undue burdens. Another part of the law, which required clinics to have facilities comparable to ambulatory surgical centers, was also struck down as serving no medical purpose. Already, the law had forced more than half of Texas’ abortion clinics to close—closures that the court noted had severely strained those still open, overworking doctors and leaving patients less likely to get quality, individualized care. “These effects would be harmful to, not supportive of, women’s health,” Justice Steven Breyer wrote in his majority opinion.

The decision was largely seen by legal scholars as a win for reproductive rights activists—one that placed limits on what could be considered an undue burden under Casey.

But when future Supreme Court cases about abortion restrictions arise, as they inevitably will, a more conservative court may define ”undue burdens” differently.

Scalia had died before the Whole Woman’s Health decision, and Gorsuch’s appointment is widely considered likely to restore the court to the conservative tilt it had before his death. Should Trump get the chance to appoint more judges, that could tilt it further.

“There’s a lot of reason to be concerned if you’re a big fan of women’s reproductive rights,” says Michael Klarman, a professor at Harvard Law School. “As soon as you overturned the trimester framework in Roe, you’re no longer in the realm of being bound by precedent.”

The court can thus see-saw back and forth on abortion decisions as conservative justices replace liberals, and liberals conservatives.

Overturning Roe entirely, on the other hand, would require a judicial about-face that so far, in 44 years, the court has avoided. When Casey presented a chance to overturn it, the court—which at that time consisted of eight Republican-nominated justices and only one Democratic-nominated one —instead re-affirmed it, much to anti-abortion activists’ surprise.

“They said essentially, ‘Look, the consensus of the country hasn’t changed; nothing is different about abortion in 1992 than it was in 1973, other than the makeup of the court,” says Cantor at UCLA. “The way they saw it, overturning Roe put them in massive danger of delegitimizing the court in the public’s eyes. If you start taking apart decisions that are highly controversial just because you don’t personally like them, you could end up destabilizing 200-plus years of an American institution that keeps people behaving properly. Law isn’t a rule of nature, like gravity. It only works if people believe in it.”

A Roe reversal is possible. Former Chief Justice William Rehnquist made no secret of his desire to do away it, and Scalia, in his Casey dissent, argued that it should be overturned, writing that since the Constitution doesn’t mention abortion specifically, it should be up to states to decide. (Critics of that argument note that the Constitution doesn’t mention marriage, either, but the court has felt free to strike down states’ bans on interracial and, more recently, same-sex marriage.) Like Scalia, Gorsuch is what’s known as a legal textualist, interpreting the law based on the words as written, not their perceived intent; he called called the late justice ”a lion of the law” in a tribute published last year in the Case Western Reserve Law Review. If Trump appointed enough justices like him—in theory, he might need just one more appointment— and the right case came up, the court could conceivably follow Scalia’s original line of thinking and overturn Roe.

At least a few states seem intent on bringing forth such a case. “Some of these [laws] we’re seeing do want to make a direct challenge to Roe,” says Janet Crepps, senior counsel with the Center for Reproductive Rights. She points to North Dakota’s 2013 law banning abortions after six weeks—at which point a fetal heartbeat can be detected, but many women don’t even yet know they’re pregnant. “North Dakota’s whole defense was that they should be given a trial to put up all these new facts on why Roe should be overturned,” she explains. A federal appeals court struck the law down, and last year the Supreme Court declined to review it.

Crepps says it’s too early to know what will happen in the next few years. In theory, Whole Woman’s Health has made it harder for states to pass abortion restrictions, but the political climate—a president who vows to try to overturn Roe, a Congress poised to defund Planned Parenthood—may embolden state lawmakers seeking to limit it. “We’re waiting to see what the legislatures do in the various states,” says Crepps. She points to the rash of laws banning abortion after 20 weeks—16 states already have such laws on the books—even though that’s well before viability, as one of the more recent tactics get the Supreme Court to re-think Roe.

But even if the court takes up such a case, Klarman at Harvard says an overturn of Roe would only inflame the abortion debate further and generate a backlash against the court—something its justices likely realize. “To me it’ll be a calculation of, ‘How much of a price are we going to pay with regards to the legitimacy of the institution?’” The Supreme Court, he said, operates under the notion that its justices are somehow bound not by political views but by the law, and the president’s promise to choose justices with the express purpose of overturning Roe would make it tough for the court to do so without abandoning its apolitical veneer. “If they’re constantly overruling past decisions, people are going to see it’s a canard. It’s all politics.”

Watch This Now: Gorsuch Warns Against Judges Being ‘Secret Legislators’

Gorsuch Warns Against Judges Being 'Secret Legislators'

An oil pipeline runs from an on-shore tie-in facility, the production and metering facility for the Caelus Energy Oooguruk Development Project.

Photographer: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg

The Monumentally Expensive Quest to Pull Off an Alaskan Oil Miracle

Caelus Energy and Jim Musselman are braving polar bears, bitter cold and harsh economic reality.

It’s hard to tell where the world ends here on the Alaska N

No comments:

Post a Comment