An interview with The EconomistBrazil’s accidental, consequential president

Michel Temer would rather be unpopular than populist

MOST presidents in Michel Temer’s situation would be called “embattled”. Brazil has yet to recover from its worst recession on record. Some of the president’s closest associates face accusations in the country’s biggest-ever scandal. His approval rating is below 30%; many Brazilians regard his presidency as illegitimate.

Yet, in an interview with The Economist, on a Saturday in a nearly deserted presidential palace, Mr Temer seemed anything but embattled. Collar unbuttoned, sleeves rolled to his elbows, the energetic 76-year-old was untroubled by the scorn that Brazilians heap upon him. Asked about the slogan “Temer out!”, spray-painted on a flyover that he passes on his commute between his official residence and his office, Mr Temer called it “proof of democracy’s vibrancy”. He could arrange to have it painted over, but would not dream of it.

He was not expecting to become president. Until last May, he was the largely powerless vice-president under Dilma Rousseff, of the left-wing Workers’ Party (PT). He took over when she was impeached for manipulating government accounts. To her allies, Mr Temer is a golpista (coup-monger). To many other Brazilians, he is a typical member of the corrupt political class responsible for a vast bribery scheme centred on Petrobras, the state oil firm. Ms Rousseff was driven out of office by anger about that scandal, though she was not directly implicated, rather than by the technical offence with which she was charged. Some think Mr Temer’s presidency will also come to a premature end.

His jauntiness comes from his confidence that history will vindicate him. A member of the centrist Party of the Brazilian Democracy Movement, he is piloting reforms through congress to clear away obstacles that have blocked Brazil’s progress for decades. Although Mr Temer will have been president for less than three years by the time he is due to leave office in early 2019, he says he will hand on to his successor a country that is “back on track”.

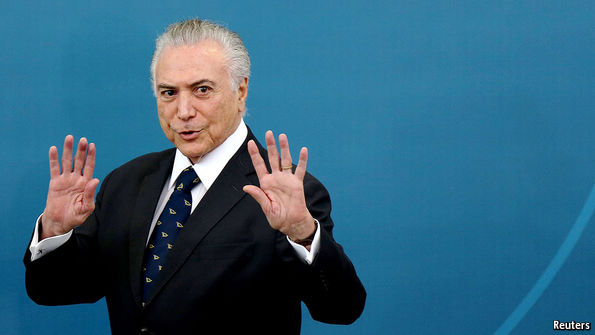

As if to persuade his audience that what seems fantastic is real, he emphasises his points with the gestures of a stage magician. His government has passed a constitutional amendment to freeze federal spending in real terms for 20 years. It will soon reform the pension system. Those measures will help contain the increase in Brazil’s massive public debt, one of the main threats to its long-term prosperity.

They face fierce opposition, especially from the PT and from trade unions, which contend that the government is balancing its accounts on the backs of the poor. Mr Temer retorts that without such action the federal government will suffer the fate of states like Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais, “which are virtually bankrupt because of public pensions”. He points to himself as a “clear example of premature retirement”: he has been drawing a generous pension since he stopped working as a prosecutor in São Paulo more than two decades ago. Far from hurting the poor, the reforms will protect “the future of all our social programmes”, he insists. He would “rather be unpopular now than a populist”.

So far, congress has largely gone along with his plans. The government has “an extremely solid parliamentary base”, Mr Temer says. Emboldened by that support, he intends to begin an assault on the Mussolini-era labour laws. He is pushing a bill that would relax restrictions on employing temporary workers and let agreements between unions and employers override some rules in the labour code. On March 7th he presented a plan to simplify the tax law, whose complexity discourages enterprise, and to put out to tender 45bn reais ($14bn) in infrastructure projects.

Many Brazilians scoff at the idea that Mr Temer could be part of the solution. The prosecutor-general, Rodrigo Janot, will soon present a list of politicians he wants investigated as part of the Lava Jato (Car Wash) investigations into the Petrobras scandal. They are expected to include people close to Mr Temer, as well as figures from rival parties, including the PT. Separately, the electoral tribunal is investigating whether the re-election campaign of Mr Temer and Ms Rousseff in 2014 benefited from dodgy donations. An executive jailed in the Lava Jato investigation testified that he and Mr Temer had discussed campaign donations.

Voters suspect that the president would like nothing more than to thwart investigations that could threaten him. Perhaps, but he gives a good impression of being their biggest fan. Lava Jato, he says, is the “best example” of a process that is strengthening Brazil’s national institutions. As for the case against his re-election campaign, he has “full peace of mind”; all the donations were registered legally. If so, there is little to stop Mr Temer from serving out his term. This accidental president could end up being a pretty consequential one.

Yet, in an interview with The Economist, on a Saturday in a nearly deserted presidential palace, Mr Temer seemed anything but embattled. Collar unbuttoned, sleeves rolled to his elbows, the energetic 76-year-old was untroubled by the scorn that Brazilians heap upon him. Asked about the slogan “Temer out!”, spray-painted on a flyover that he passes on his commute between his official residence and his office, Mr Temer called it “proof of democracy’s vibrancy”. He could arrange to have it painted over, but would not dream of it.

Latest updates

His jauntiness comes from his confidence that history will vindicate him. A member of the centrist Party of the Brazilian Democracy Movement, he is piloting reforms through congress to clear away obstacles that have blocked Brazil’s progress for decades. Although Mr Temer will have been president for less than three years by the time he is due to leave office in early 2019, he says he will hand on to his successor a country that is “back on track”.

As if to persuade his audience that what seems fantastic is real, he emphasises his points with the gestures of a stage magician. His government has passed a constitutional amendment to freeze federal spending in real terms for 20 years. It will soon reform the pension system. Those measures will help contain the increase in Brazil’s massive public debt, one of the main threats to its long-term prosperity.

They face fierce opposition, especially from the PT and from trade unions, which contend that the government is balancing its accounts on the backs of the poor. Mr Temer retorts that without such action the federal government will suffer the fate of states like Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais, “which are virtually bankrupt because of public pensions”. He points to himself as a “clear example of premature retirement”: he has been drawing a generous pension since he stopped working as a prosecutor in São Paulo more than two decades ago. Far from hurting the poor, the reforms will protect “the future of all our social programmes”, he insists. He would “rather be unpopular now than a populist”.

A better class of politician

A constitutional lawyer by training, Mr Temer dreams of reforming Brazil’s dysfunctional political system. Despite his success in congress, he, like other presidents, has found it hard to manage a legislature composed of 28 parties, many of them machines for extracting patronage. “Brazil has no parties, only acronyms,” he complains. The number could be cut by introducing a British-style first-past-the-post electoral system or voting by party lists rather than for individual candidates, he muses. Congress is considering the introduction of a 3% nationwide vote threshold for parties to enter the legislature and a ban on coalitions that bring in small parties. Both would be significant reforms.Many Brazilians scoff at the idea that Mr Temer could be part of the solution. The prosecutor-general, Rodrigo Janot, will soon present a list of politicians he wants investigated as part of the Lava Jato (Car Wash) investigations into the Petrobras scandal. They are expected to include people close to Mr Temer, as well as figures from rival parties, including the PT. Separately, the electoral tribunal is investigating whether the re-election campaign of Mr Temer and Ms Rousseff in 2014 benefited from dodgy donations. An executive jailed in the Lava Jato investigation testified that he and Mr Temer had discussed campaign donations.

Voters suspect that the president would like nothing more than to thwart investigations that could threaten him. Perhaps, but he gives a good impression of being their biggest fan. Lava Jato, he says, is the “best example” of a process that is strengthening Brazil’s national institutions. As for the case against his re-election campaign, he has “full peace of mind”; all the donations were registered legally. If so, there is little to stop Mr Temer from serving out his term. This accidental president could end up being a pretty consequential one.

No comments:

Post a Comment