CHILE: The Barnes House

U.S. Embassy names residency for former Ambassador Harry G. Barnes

Barnes earned Pinochet’s enmity for promoting human rights and democracy; the dictator refused to meet with him; called Barnes “Dirty Harry”

National Security Archive pays tribute to Barnes by posting key documents

recorded during his ambassadorial tenure

Washington D.C., October 3, 2023 – As a diplomatic gesture to mark the 35th anniversary of the October 5, 1988, Chilean plebiscite that forced General Augusto Pinochet from power, the U.S. State Department today designated the Ambassador’s residency in Santiago as “the Barnes House”—honoring the former Ambassador Harry G. Barnes who served as U.S. chief of mission in Santiago during the last years of the Pinochet dictatorship. “The Chief of Mission’s residence will be named ‘The Barnes House,’” according to a U.S. Embassy press advisory, “to recognize Ambassador Barnes’ support of and solidarity with the Chilean people who sought to defend human rights and restore democracy to their country via peaceful and democratic means.”

During his tenure from late 1985 to the end of 1988, Barnes aggressively pushed Pinochet to return Chile to civilian rule and end the regime’s ongoing human rights violations. “The ills of democracy can best be cured by more democracy,” Barnes pointedly remarked as he presented his credentials to General Pinochet in mid-November 1985. “I quote[d] Winston Churchill to the effect that nothing is more important than human rights except more human rights,” he recalled in an oral history on his career with the Library of Congress. “Pinochet did not like that.”

Indeed, Pinochet blocked Barnes’ access to other government ministers and refused to meet with him again. In July 1986 when Barnes attended the funeral of Rodrigo Rojas, the teenage U.S. resident burned to death by a military patrol during a protest, Pinochet’s police force attacked the procession with water cannons and tear gas; the regime then falsely blamed Barnes of inciting a riot. After the U.S. Embassy began supporting the campaign of the “No” in the October 1988 referendum on Pinochet’s continuation in power, the general denounced U.S. interference and “Yankee Imperialism.” The military-controlled media in Chile took to referring to Ambassador Barnes as “Dirty Harry.” U.S. intelligence officials reported that Pinochet was considering declaring the ambassador persona non grata and “throwing Barnes out of the country.”

Barnes’ effective efforts to call attention to human rights violations and forcefully support opposition to the dictatorship contrasted sharply with the earlier history of Washington’s support for the military coup and the consolidation of the Pinochet regime. “In a dark historical saga full of U.S. villains in Chile,” notes Peter Kornbluh who directs the Archive’s Chile Documentation Project, “Ambassador Barnes stands out as a true American hero.”

As a historical tribute to Ambassador Barnes, the Archive is posting a small selection of documents on his role in the Rodrigo Rojas case, where he used his close connections to Chilean officials to expose Pinochet’s efforts to cover up the military’s culpability in this human rights atrocity, as well as his efforts to thwart Pinochet’s Machiavellian plot to foment a violent second coup when the “No” vote won and the general lost the plebiscite on continuing his dictatorship.

THE DOCUMENTS

Document 1

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

In a secret set of instructions, Secretary of State George Shultz sends Ambassador Barnes a guidance statement for the goals of his ambassadorship. “It appears likely that President Pinochet will try to remain in office beyond 1989 and will not negotiate willingly with the democratic opposition,” the letter states. The United States has interests that would be best served by “the orderly restoration of democracy as speedily as possible,” and “limitation of the influence of the Chilean Communist Party.”

Document 2

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

Ambassador Barnes reports on an hour-long meeting with General Pinochet’s top deputy, General Santiago Sinclair, during which a number of topics are covered, including whether Pinochet intends to hold onto power. Sinclair accuses Barnes of being “exploited by Communists” for attending the funeral of Rodrigo Rojas. Sinclair flagrantly attempts to mislead the ambassador by denying any Army role in the burning death of Rojas, even though multiple witnesses saw the Army patrol set him on fire, along with a companion, Carmen Quintana (who survived with severe burns), and load them into a military truck.

Document 3

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

Ambassador Barnes’ decision to attend the funeral of Rodrigo Rojas angered Pinochet and his supporters—among them the ultra-conservative U.S. Senator Jesse Helms. Helms flew to Santiago to directly chastise Barnes. “You have screwed it up,” Helms told Barnes, according to this memorandum of their conversation. Helms “said he had not wanted to see me because people in Washington had told him I was advertised in Washington as someone sent to Chile to undermine Pinochet,” Barnes reported to Washington. Barnes responded that “my job was to do what I could to help promote a return to democracy and advance human rights.”

Document 4

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

Drawing on a high-level informant in the Chilean Carabineros (police service), Barnes transmits the conclusions of investigators that Chilean army officers were responsible for setting Rodrigo Rojas and Carmen Quintana on fire and leaving them for dead in a ditch. The source shared detailed information on the futile efforts by the head of the Carabineros, Gen. Rodolfo Stange, to provide Pinochet with those investigative conclusions. Pinochet refused to receive the report from Stange, and subsequently denounced Rojas and Quintana as “terrorists” killed by their “own Molotov cocktails.” The events described in the cable suggest that the cover-up of the crime emanated from the highest levels of the Pinochet regime—General Pinochet himself.

Document 5

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

Ambassador Barnes sends a comprehensive assessment of possible outcomes and scenarios related to the referendum on Pinochet’s continued rule, scheduled for October 5, 1988. One scenario repeatedly addressed is the possibility of an “auto-golpe”—a second coup—if the vote goes against Pinochet. Barnes notes that there is not “sufficient intelligence” to know Pinochet’s contingency plans for staying in power. But, he advises, “it cannot be ruled out, and we must be prepared to react to it, and swiftly, while there is still a chance it might be reversed.”

Document 6

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

On the evening of September 30, Barnes receives information on Pinochet’s planning to foment violence and stage an auto-coup on the night of the plebiscite. The information comes from a trusted friend and associate of the Embassy, Monica Jimenez, who heads the Civitas Civic Education Crusade which is monitoring the preparations for the vote; she has just met with Brigadier General Jorge Zinke who commands the Santiago military zone. Zinke has described a Communist plot to foment violence the night of the plebiscite, but he has inferred that it is really a Pinochet plot that will be blamed on the Chilean left. “The persons with whom Zinke spoke,” Barnes reports urgently to Washington, “are convinced he, for unknown reasons, was warning them of what the Army, and not the Communists, were planning to do to disrupt the plebiscite.”

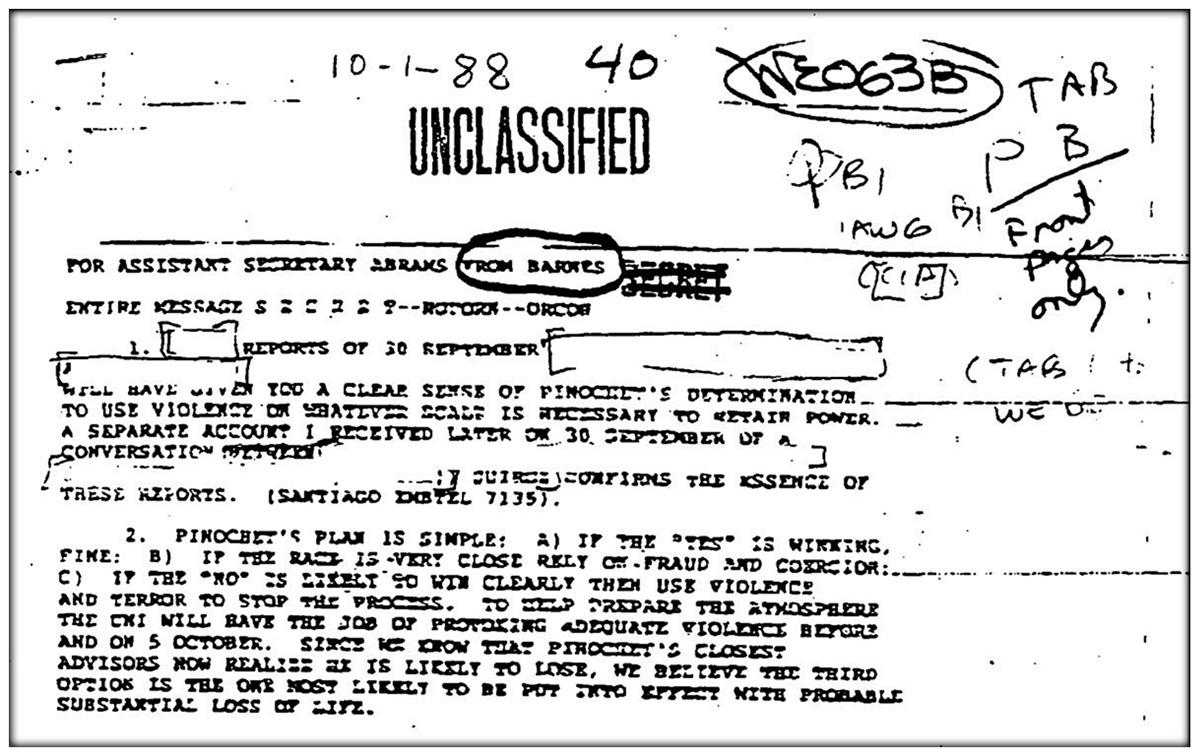

Document 7

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

Acting on information initially provided by General Zinke to Monica Jimenez, the CIA, DIA, and the U.S. Embassy began to obtain detailed intelligence from multiple sources inside the military on "Pinochet's determination to use violence on whatever scale is necessary to retain power," as Ambassador Barnes alerts the State Department. In this forcefully worded message, Barnes warns that Pinochet is planning to use "violence and terror" to stop the plebiscite if he appears to be losing, and that the result would be "probable substantial loss of life."

Document 8

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

After obtaining intelligence on Pinochet’s auto-coup plot, the Reagan Administration launches a major pressure campaign to press other members of the military regime not to implement the plan. Only a day before the plebiscite, Ambassador Barnes meets with Pinochet’s foreign minister to make sure he, and Pinochet, understand that the United States government knows what Pinochet plans to do and seriously opposes any effort to disrupt a fair vote on the continuation of his regime. “Our information comes from senior Army generals,” Barnes informs Ricardo Garcia Rodriguez. “It (the plan) has been approved by the highest levels of [Pinochet’s] government to use violence as a pretext to disrupt the plebiscite process, closing the polls, and nullifying the election.”

No comments:

Post a Comment