“After Black November”: The U.S. and the 1985 Palace of Justice Tragedy

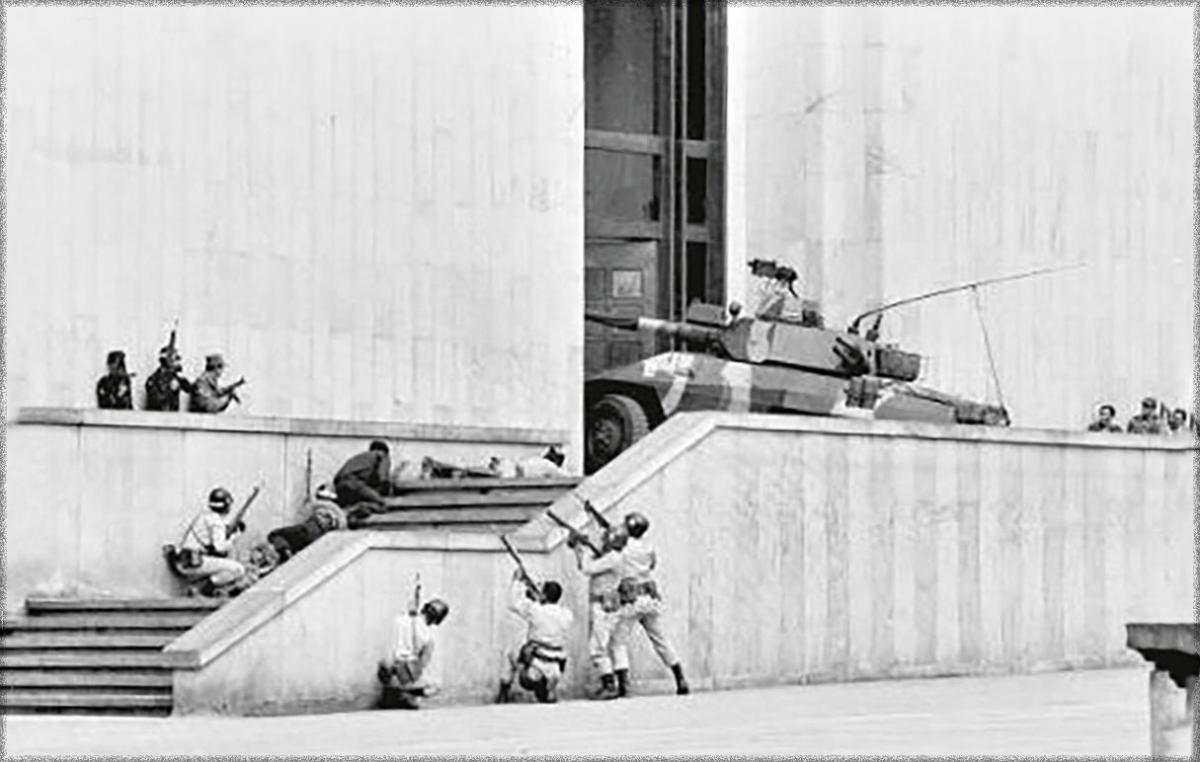

A Colombian Army cavalry regiment uses an EE-9 Cascavel armored car to breach and enter the Palace of Justice building on November 6, 1985, after it was occupied by M-19 insurgents earlier that day. (U.S. Army)

Daughter of Slain Magistrate Calls for Full U.S. Declassification on Emblematic Human Rights Case

U.S. Sent Explosives Team and C4 to Bogotá During Hostage Crisis

Colombian Military Knew Palace of Justice Was Possible Insurgent Target

President Betancur “Gave the Military a Green Light” to “Do Whatever Was Necessary”

Washington, D.C., September 19, 2023 – Colombian President Gustavo Petro should comply with the 2014 sentence of the Inter-American Human Rights Court (IACHR) and ask U.S. President Joe Biden to declassify all pertinent U.S. records on the Palace of Justice case, according to Helena Urán Bidegain, the daughter of a court magistrate believed to have been tortured and assassinated by the Colombian Army in the aftermath of the conflagration. Over 100 people perished during the episode, including 11 Colombian Supreme Court justices, most of them during Colombian military operations to retake the building from M-19 militants who stormed and occupied the Palace the morning of November 6, 1985.

Today, the National Security Archive publishes a key set of declassified U.S. documents cited in Helena Urán’s recently published book, Mi vida y el Palacio: 6 y 7 de noviembre de 1985. Among them are still-redacted copies of 38-year-old State Department cables and Pentagon intelligence reports that likely withhold crucial details about the U.S. role and what U.S. agencies knew about the actions of Colombian security forces during the military assault on the building. Urán, who earlier this year was designated a special adviser to the Colombian foreign ministry on matters of non-repetition, told the RTVC television network that she had investigated U.S. records provided by the National Security Archive and “found information that the country should know.”

Long said to have been killed in crossfire inside the Palace, in 2007 the Colombian prosecutor uncovered video footage showing Helena’s father, Carlos Horacio Urán, limping out of the burning wreckage of the building in the custody of Colombian security forces. Some of the magistrate’s possessions were later found during a search of a nearby Colombian Army installation, leading many to conclude that the auxiliary magistrate was detained and killed by the military, and that his body was later placed inside the still-smoldering Palace of Justice building to deceive investigators and cover up the military’s responsibility for his death.

“I think it would be a good moment for President Gustavo Petro to make a formal declassification request to President Biden as a way of a responding to the sentence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights,” said Helena Urán in an interview last week with RTVC. “I think that to completely declassify those archives would be a great support to the peace process, to reconciliation, to non-repetition, and to the strengthening of democracy in Colombia.”

A previous Archive posting featured a 1999 cable from the U.S. Embassy Bogotá indicating that the Colombian Army was responsible for deaths and disappearances during the Palace of Justice case. The cable said that soldiers under the command of Col. Alfonso Plazas Vega, who in 1985 was in charge of the Bogotá-based Escuela de la Cabellería (Cavalry School), “killed a number of M-19 members and suspected collaborators hors de combat [“outside of combat”] including the Palace's cafeteria staff.”

Colombia’s truth commission, which last year published its final report, made the Palace of Justice case a top priority of a March 2021 request asking Biden to expedite the declassification of U.S. records on more than 50 years of war in Colombia. The 2014 IACHR sentence said the Colombian state was responsible for human rights violations and the disproportionate use of force during the assault and had violated the rights of victims by failing to investigate and bring to justice those responsible. To date, only two military officials, including Plazas Vega, have been convicted for acts related to the Palace of Justice assault. So far, no one has been held responsible for the killing of Carlos Urán. The state’s failure to fully investigate the Palace of Justice case is why members of the Urán family, including Helena and two of her sisters, filed a complaint in U.S. federal court under the Torture Victims Protection Act (TVPA).

Portions of the documents that have been released reveal tantalizing clues and fractions of details that if fully declassified could help clarify what happened to victims like Magistrate Urán and others, including members of the building’s cafeteria staff, believed to have been disappeared, tortured and killed by Army intelligence officials after surviving the Army’s violent assault on the building.

One U.S. military report, for example, indicated that Colombian Army intelligence knew that the Palace of Justice was a likely M-19 target more than a week before the occupation. (Document 5) Colombian security forces had “surprised” the M-19 at the beginning of the crisis, according to one of the U.S. Embassy’s first readouts on the unfolding crisis and were “’in charge’ of the situation” only hours after it began. The same cable said that U.S. personnel were in touch by telephone with at least two people who were trapped inside the building, including one inside the office of the Supreme Court, who provided updates on the situation. (Document 2)

Other records describe actions taken by the U.S. in response to emergency appeals for support from Colombian security forces during the crisis. A request for assistance shortly after the initial M-19 assault, for example, led U.S. Southern Command (Southcom) to dispatch a C-130 aircraft and a six-person “support team” carrying high-powered C4 explosives and detonating cord to Bogotá, leading Helena Urán to ask whether it was the U.S. that supplied the technology used just a few hours later to blow open a large metal door on the third floor of the building—an explosion that was determined to have caused many civilian casualties. (Documents 4 and 6) The U.S. also pondered a Colombian request for “asbestos suits” so that security forces could continue “pressing their efforts” inside the “fire gutted building.” (Document 7)

Other records shed light on the Betancur government’s decision to take a hard line against the M-19 and the President’s refusal to negotiate with the militants, a decision that was immediately known to the Embassy. Betancur “gave the military a green light, telling them to do whatever was necessary to resolve the situation as quickly as possible,” said a U.S. military report sent on the afternoon of November 6. (Document 3)

In another example, a detailed set of U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) “Talking Points” written nearly two weeks later said that M-19 “reportedly intended only to stage a publicity-generating operation that would enable it to criticize the government and promote its cause.” The Army nevertheless “launched a massive counterattack, which left all of the guerrillas, 15 of 24 Supreme Court justices, and about 55 others dead.” (Document 10)

While few would debate the now widely accepted fact that Betancur gave carte blanche to the Colombian security forces to end the occupation by force, causing numerous casualties, declassified documents from the weeks and months following the assault shed light on the internal dynamics the led a proponent of peace and dialogue like Betancur to take a hard line against the M-19 insurgents.

The CIA’s National Intelligence Daily for November 13, one week after the disaster, said that Betancur’s reluctance to deal with the M-19 was probably due to “fear that anything short of a full-scale retaliation would have worsened relations with the military,” noting that his handling of the episode “probably will weaken his popular standing.” (Document 9) Similarly, the CIA talking points from November 18 said that Betancur’s “fear that failure to act forcefully would anger military leaders” was one of the main things behind his decision to let security forces storm the building rather than negotiate. (Document 10)

One month after the assault, a detailed Embassy missive on the affair titled “After Black November” took a more nuanced view of the theory that Betancur acted out of concern for his standing among the military. Most of the country’s top leaders, the Embassy suggested, agreed “that negotiations would unacceptably damage the legitimacy and public respect of the government.” The Embassy said that it had “no reason to believe that Betancur and his generals were ever on opposite sides of the issue.” (Document 11)

The “After Black November” cable also included some ominous speculation about the future of civil-military relations in Colombia, noting that the Embassy had “begun to suspect that some of the leftist propaganda about security force ‘provocations’, plots against the peace process, undermining of GOC-FARC truce, and assassinations of individual leaders, contain a germ of truth … at least in the limited sense that the military may be provoking some confrontations with the guerrillas.” The military was said to be anticipating “the swing of political opinion towards more forceful tactics against insurgents.”

The military would have “a free hand” against insurgents when Betancur left office in 1986, according to the Embassy’s analysis of the situation. “The military leadership,” such as Colombia’s armed forces chief, Gen. Augusto Moreno Guerrero, was “waiting out the Betancur term” and, according to Moreno, “hoping … after our Carter, we have a Reagan.” (Document 11)

“President Petro has a historic opportunity to do what no other Colombian president has been able to do: to finally bring justice to the family of Carlos Urán and to all of the victims of the 1985 Palace of Justice tragedy,” said Michael Evans, director of the Archive’s Colombia Documentation Project. “The first step is to recover the historical truth that, 38 years later, remains hidden in U.S. archives.”

Note: U.S. government communications such as State Department cables and DIA intelligence information reports bear date/time stamps reflecting Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) and thus the time in Bogotá would be six hours earlier. This means that some documents dated November 7 were actually sent in the late hours of November 6.

THE DOCUMENTS

Document 1

Freedom of Information Act request

Less than three years before the Palace of Justice seizure, a U.S. Embassy cable identifies and describes units of the Colombian security forces involved in counter-terrorism operations. Noting the “considerable overlapping of effort and potential conflicts” among Colombian police and military units, the Embassy says that “in practice, the senior local Colombian Army official has assumed control in serious terrorist incidents,” citing the roles of the Military Institutes Brigade (BIM) and the 3rd Brigade, respectively, in the 1980 seizure of the Dominican Embassy and the January 1982 Aerotal hijacking in Cali, in both cases by M-19 guerrillas.

Document 2

Freedom of Information Act request

A U.S. Embassy report on the takeover of the Palace by M-19 guerrillas from early afternoon on November 6 indicates that U.S. personnel are in touch by telephone with at least two people inside the building, including someone inside the Supreme Court office who was said he was “guarding himself.” A top Colombian military intelligence official told the U.S. defense attaché that Colombian forces had “surprised” the M-19 militants at the start of the operation and were now “in charge” of the situation, even as gunfire continued. Security has been increased for a nearby conference organized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Document 3

Freedom of Information Act request

In the middle of the afternoon on November 6, one of the first U.S. military attaché reports on the unfolding crisis describes the initial military assault on the building just a few hours after the M-19 seized control. A U.S. military source indicated that President Betancur “gave the military a green light, telling them to do whatever was necessary to resolve the situation as quickly as possible.” The attaché says that Betancur’s “unleashing of the military is particularly significant” and predicts that the President “is about to come out a winner.”

Document 4

Freedom of Information Act request

On the evening of November 6, the U.S. military attaché files a report on Colombia’s apparent request for U.S. military assistance, made around 4:00 p.m. on November 6, and the subsequent dispatch by U.S. Southern Command of a U.S. C-130 aircraft to Colombia, scheduled to arrive in Bogotá at 8:30 p.m. that evening. Redactions in the document obscure the nature of the request and the substance of the U.S. response, although U.S. personnel appear to be under instructions “restricting them to airport.” According to the report, “Current situation appears to be that the President of the Supreme Court, together with 10 other hostages, are holed up behind a metal door in the Palace of Justice.”

Document 5

Freedom of Information Act request

In a report filed late on November 6, the U.S. military attaché indicates that Colombian security forces had been “alerted by intelligence over a week ago that the Palace of Justice was one of the possible targets of the M-19” and thus “reacted swiftly to prevent a complete take over.” Around noon, two trucks “containing weapons and M-19 supporters” had been “intercepted and detained,” according to the report. “It appears that the Colombian government is taking a hard line in this situation,” the report concludes.

Document 6

Freedom of Information Act request

A U.S. military “support team” consisting of “3 explosive experts and 3 communications experts” arrived in Bogotá at 11:50 p.m. on November 6 carrying “C4 explosives” and detonating cord “pending expresse need and necessary advise by experts to Colombian team,” according to this report from the U.S. military attaché in Colombia. Ongoing fires at the Palace of Justice mean that “it is not possible at this time to place charges,” the report adds. Earlier, three charges had been set off in front of the Palace “followed by heavy firing on the front of the building by 3 Castavel armored vehicles.” Another charge had been set off inside the building after some 50 troops breached the entrance. The Colombian Army engineer officer who received the U.S. assistance team told them that “the decision was made to end the situation tonight.”

Document 7

Freedom of Information Act request

Around 8:00 a.m. on November 7, as “intense heat from the fires prevents Colombian security forces from pressing their efforts,” the U.S. has been asked to “determine the availability for loan of 12 asbestos suits for use in the fire gutted building.”

Document 8

Freedom of Information Act request

A U.S. Embassy wrap-up of the Palace of Justice episode reports the deaths of Supreme Court President Alfonso Reyes Echandia and Magistrate María Inés Ramos by M-19 leader Andrés Almarales, adding that “The surviving guerrillas have all been taken prisoner.”

Under the heading, “Local Flavor,” the Embassy relates how a cocktail party scheduled for the afternoon of November 7 at the Soviet Embassy went on as scheduled, despite the crisis at the Palace of Justice. Asked by a U.S. official whether increased security at the event “reflected the current incident,” a Soviet official “acknowledged that the Soviet Embassy was probably not a prime target,” adding that “with so many different ‘líneas políticas’ [political factions] in this country, even the Soviets can not rule out the chance that some group will make an attempt.”

Document 9

CIA CREST database

Despite an earlier assessment by the U.S. military attaché that Betancur would come out of the Palace of Justice debacle as a “winner” (see Document 2), here the CIA finds in the National Intelligence Daily (NID) that his handling of the episode “probably will weaken his popular standing.” There has been a “mixed reaction” in the country, with many expressing support for the President’s hardline approach, while others have been more critical, including “30,000 unionized court employees” who called for a strike over “the government’s refusal to negotiate for the release of the hostages.” Betancur’s reluctance to strike a deal with the M-19 was probably due to “fear that anything short of a full-scale retaliation would have worsened relations with the military.”

Document 10

CIA CREST database

These CIA talking points note that the M-19 “reportedly intended only to state a publicity-generating operation that would enable it to criticize the government and promote its cause. The Army, however, launched a massive counterattack, which left all of the guerrillas, 15 of 24 Supreme Court justices, and about 55 others dead.”

Document 11

CIA CREST database

This fascinating cable is the U.S. Embassy’s assessment of Colombia’s internal security situation a month after the Palace of Justice burned down. The Embassy’s predicts “a cyclical swing to the right in Colombian politics,” “increased reliance on military action to restore public order” and a “request for an increase in [U.S.] security assistance.” Characterizing these as “generally favorable prospects,” the Embassy anticipates “the continuation of present [U.S.] policies toward Colombia” and of Colombia’s “own democratic traditions.”

Regarding the decision to launch the military attack to retake the building, the Embassy says that “Many find it impossible to believe that Betancur, the endlessly-patient man of peace, would order the recapture of the Palace of Justice and accept the near certainty of the hostages’ deaths,” while “alternate theories focus on the military, and the allegedly irresistible pressure they were said to have applied” on the President. In the Embassy’s view, the decision-making process was “more complex” and “more typically Colombian,” with most of the country’s top leaders, including Betancur, in agreement “that negotiations would unacceptably damage the legitimacy and public respect of the government.” The Embassy says it has “no reason to believe that Betancur and his generals were ever on opposite sides of the issue.”

Ominously, the Embassy says it has “begun to suspect that some of the leftist propaganda about security force ‘provocations’, plots against the peace process, undermining of GOC-FARC truce, and assassinations of individual leaders, contain a germ of truth … at least in the limited sense that the military may be provoking some confrontations with the guerrillas.” These suspicions “indicate that some within the military had anticipated the failure of the peace process and the swing of political opinion towards more forceful tactics against insurgents.”

“The Colombian military can now anticipate a relatively free hand against all the guerrillas except the FARC,” with whom there were ongoing negotiations, “and a free hand even against them after Betancur leaves office in only nine months.” Colombia’s armed forces chief, Gen. Augusto Moreno Guerrero, told the U.S. military attaché that “The military leadership is waiting out the Betancur term and hoping … after our Carter, we have a Reagan.”

Document 12

Freedom of Information Act request

A panel of judges has concluded that President Betancur acted within his presidential powers in ordering a military counterattack but also found that he “should have established a dialogue with the attackers.” Their report did not clarify “why military and police protection was withdrawn from the Palace the day of the attack” and was unable to prove widespread rumors that the seizure of the building was a conspiracy between the M-19 and narcotraffickers from the Medellín Cartel. The report calls on the military to investigate reports about two insurgents who were seen leaving the building but had since disappeared. “We continue to believe,” the Embassy comments, “that the Palace of Justice attack will become one of the great mysteries of Colombian history and the frequent (but probably fruitless) object of conspiracy theorists.”

No comments:

Post a Comment