A row over the colours in Argentina’s flag

Putting the vex in vexillology

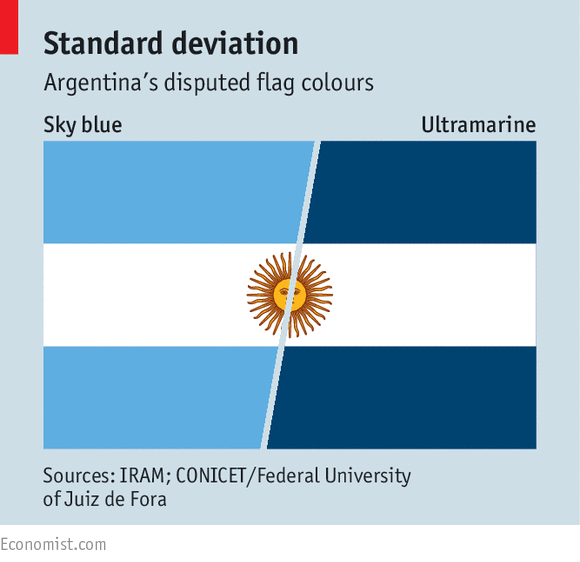

But are they saluting the right shade of blue? A study published in a recent edition of Chemistry Select, a peer-reviewed journal, suggests not. Researchers at Argentina’s scientific research council (CONICET) and Brazil’s Federal University of Juiz de Fora examined silk threads from what is thought to be the oldest surviving flag, the enormous but faded San Francisco flag. The shocking discovery: its blue was ultramarine, a much darker pigment.

Latest updates

After the Unitarians’ triumph, most Argentines assumed that Belgrano’s flag must have been light blue, despite his reluctance to back the faction. That belief was shaken when researchers took a close look at the San Francisco flag, which they say was made in Europe in 1814. Though it has been bleached by age and by dust stirred up by decades of sugar-cane harvests, scientists used chemical analysis, X-rays and spectroscopy to determine that the pigment in its blue stripes was made from lapis lazuli, which produces the darker shade.

Some historians detect in the colour shift a sneaky attempt to rehabilitate De Rosas’s reputation. Juan Pablo Bustos Thames, author of a book about the San Francisco flag and owner of a full-scale (sky-blue) replica, says the scientists ignored contemporary documents that attest to a lighter colour. Manuel Belgrano, a descendant of the independence hero, says it is unthinkable that his ancestor would have favoured ultramarine. “There’s no doubt about the colour”, he told Clarín, a newspaper.

Whatever the truth, Argentines will not soon wave ultramarine flags. In 2002 IRAM, the national standard-setting agency, confirmed the lighter colour by specifying its co-ordinates in the Lab colour system. It also set out how thick the stripes should be and how the sun should look. A decree in 2010 by the then-president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, enshrined those standards in law. Argentines are not about to change their stripes, whatever the chemists say.

No comments:

Post a Comment