How an Argentinian man learned his 'father' may have killed his real parents

From 1976 to 1983, hundreds of babies were taken from the ‘disappeared’ and raised by military families. Guillermo Pérez Roisinblit was one – and the man who raised him worked at the base where his parents were murdered

When he was a child, Guillermo’s parents nicknamed him “the Jew”.

Theirs was not a peaceful home: air force intelligence officer Francisco Gómez beat his wife Teodora Jofre frequently. “I saw him threaten her with a knife, hit her with a rifle butt, throw her on the floor and shout he would put a bullet in her,” Guillermo eventually told a court in Buenos Aires, years later.

On school holidays, Gómez would take Guillermo to spend the day at the Buenos Aires Regional Intelligence (Riba) air force base. Fellow agents took the boy out for ice cream or let him play with their unloaded guns.

Eventually, Jofre could stand her husband’s abuse no longer, and the couple separated; Guillermo lived with Jofre and only saw Gómez on weekends.

Guillermo’s world was turned upside down at age 21 when a young woman tracked him down at the fast-food outlet where he worked in the outlying Buenos Aires district of San Miguel.

“I told her I was busy working,” Guillermo recalls now. “So she sat down at a table, and wrote me a note.”

The note read: “My name is Eva Mariana Pérez, I am the daughter of desaparecidos. I’m looking for my brother. I think he might be you.”

According to human rights campaigners, 30,000 people were made to “disappear” by Argentina’s 1976-83 dictatorship, mostly young opponents of the bloody regime. Of these, between 200 and 300 were victims of the Riba intelligence unit where Guillermo played as a child.

But killing the pregnant women was a crime that even Argentina’s military men – who referred to themselves in self-aggrandising speeches as defenders of “western and Christian civilisation” – couldn’t bring themselves to commit.

Instead, they kept pregnant activists alive until they gave birth, murdering them afterwards and handing their babies to childless military couples to raise as their own. It was, in a macabre sense, the military’s ultimate victory against a despised enemy they had decided to annihilate completely. It is estimated some 500 children were born under these circumstances.

Looking up from the note he had just been handed, Guillermo told Mariana he was not the brother she was looking for. His surname was Gómez, not Pérez. Plus, he knew who his parents were. But then Mariana showed him an old photo of her father.

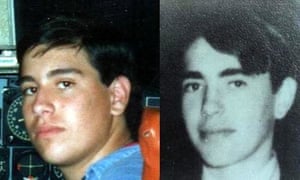

“It was like looking at a picture of myself,” says Guillermo, pulling out his smartphone to show the composite photo he now carries everywhere. On the left, a colour picture of himself at age 21, on the right, the black and white picture of his father at nearly the same age. They look like twins.

Mariana told Guillermo how their real parents, Patricia Roisinblit and José Manuel Pérez Rojo, were kidnapped by a military death squad in October 1978 and taken to the Riba intelligence base.

Patricia, a 25-year-old Jewish student of medicine, was eight months pregnant with Guillermo.

Her firstborn daughter Mariana was a 15-month-old baby at the time. Somehow Patricia managed to convince her abductors to release her baby girl into the hands of relatives. Patricia was murdered in secret shortly after giving birth to Guillermo. His real father was never seen again either.

The crimes of Argentina’s dictatorship cut a deep scar in the country’s collective memory, one that four decades later still refuses to heal.

In the past 10 years alone, more than 600 former military officers have been sentenced for human rights crimes; 1,000 more still face trial, while 57 others remain on the run, the subject of international arrest warrants.

The passage of time has given Argentina’s search for justice an added urgency: many witnesses and perpetrators of dictatorship atrocities are well into their 90s and 227 suspects have died before their cases reached sentencing in the last decade.

This May Guillermo took the stand in a hushed Buenos Aires courtroom to testify in the case he has brought against Gómez – the man he grew up calling “father” for 21 years – for the murder of his parents.

Among the accused in Guillermo’s case were a number of ageing former air force officers, including 90-year-old former air force chief Omar Graffigna, one of the members of the military junta that ruled Argentina.

And one of the key witnesses is Guillermo’s nonagenarian grandmother, Rosa Roisinblit, who was in court throughout as the horrific circumstances of her grandson’s early life were pieced together.

“I didn’t have a happy childhood,” Guillermo told the judges, wringing his hands together, eyes closed.

Among those who testified in recent weeks is Miriam Lewin, a survivor of the Esma camp, the Navy School of Mechanics in the city of Buenos Aires where 5,000 people died during the dictatorship.

Roisinblit had been taken to the Esma “maternity ward” to give birth, and the officers there brought Lewin and Roisinblit together because they knew each other from before. Lewin begged for Roisinblit not to be sent back back to Riba after giving birth.

“We suspected they’d kill her,” Lewin told the courtroom. Her request was ignored.

But the all-powerful military had not counted on the strength of the grandmothers of the babies they were abducting. The women banded together nearly four decades ago, naming themselves the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, after the main square in front of the presidential palace in downtown Buenos Aires where they demonstrated.

So far, they have been able to locate and identify by DNA tests 120 of their abducted grandchildren.

Among these courageous women is Patricia’s mother, Rosa Roisinblit. Helping herself along with a walking stick, Rosa sits down with her grandson Guillermo for an interview in the old building where the Grandmothers have their offices. Aged 96, thin and tiny, she seems almost too frail to handle the chill of the current Buenos Aires winter, let alone testify against Gómez as she did two months ago for the murder of her daughter. The trial is expected to last until at least October.

In a whisper of a voice that somehow conveys the determination with which she pursued Gómez for decades, Rosa recalls how Patricia’s disappearance launched her into a whirlwind of activism until she became the vice-president of Grandmothers.

An obstetrician by profession, she has one major regret.

“I helped bring so many babies into this world, but I couldn’t be there for the birth of my own grandson.”

Guillermo’s adaptation to his biological family has been slow, but the warm glow between him and his grandmother is readily apparent as they squeeze hands throughout the interview. “My grandson was born already 21 years old,” says Rosa. “It’s not the same as knowing him since he was a baby, when you get to play grandmother, take him to the park. I can’t take him to the merry-go-round when he’s already a man.”

Guillermo, now 37, a senate employee and law student, recalls how he confronted Gómez with the truth. “At first he denied everything,” he says, his voice dropping in volume. It wasn’t until the fourth confrontation, while driving together that Gómez finally cracked.

“He suddenly burst into tears, admitting I was the son ofdesaparecidos, telling me that my mother had been Jewish,” says Guillermo.

Suddenly all fell into place. The violence. The nickname. Eventually Guillermo realized that the Riba unit where he played as a child was the very place where his real parents had been murdered. And that the man he had thought of as his father had taken part in their deaths.

Guillermo sighs heavily as he continues. “He asked me to rest assured nothing bad happened to my mother while she was pregnant, though he couldn’t say the same about my father. He said he took care of my mother, that he brought her food secretly on weekends. It was too much information for me.”

Guillermo has since changed his surname from Gómez to Pérez Roisinblit, a combination of his biological parents’ names. Apart from seeing him in court this May, he has had no contact with Gómez for years, after the former intelligence agent threatened both him and his biological grandmother.

He maintains a difficult realtionship with Teodora Jofre, who claims she was not aware he was the child of desaparecidos, believing he was the illegitimate child of one of her husband’s comrades.

Despite her 96 years, Rosa says she is not about to give up anytime soon the fight for the missing grandchildren her association is still looking for.

“The strength comes from the love for your children,” she says. “If I had stayed home crying for the disappearance of my daughter I would have died long ago.”

No comments:

Post a Comment