https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/argentina-lawmakers-now-have-2-years-turn-economy-around?id=743c2bc617&e=1bd154cf7d&uuid=9eace7ef-46c8-418b-9547-63873414cac2&utm_source=Topics%2C+Themes+and+Regions&utm_campaign=e0e3c4bdf9-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2017_10_31&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_743c2bc617-e0e3c4bdf9-53655957&mc_cid=e0e3c4bdf9&mc_eid=1bd154cf7d

Time to bury Che Guevara for good

The left needs a more democratic icon

ON OCTOBER 9th 1967 the Bolivian army, with the CIA in attendance, shot Ernesto “Che” Guevara in cold blood, on the orders of Bolivia’s president. Thus ended his short-lived attempt to ignite a guerrilla war in the heart of the Andes. Fifty years on, Bolivia’s current president, Evo Morales, and several thousand activists assembled there this week to honour Guevara’s memory.

In death Che, with his flowing hair and beret, has become one of the world’s favourite revolutionary icons. His fans span the globe. Youthful rebels wear T-shirts emblazoned with his image. Ireland this month issued a commemorative stamp. But it is in Latin America where his influence has been greatest, and where his legacy—for the left in particular—has been most damaging.

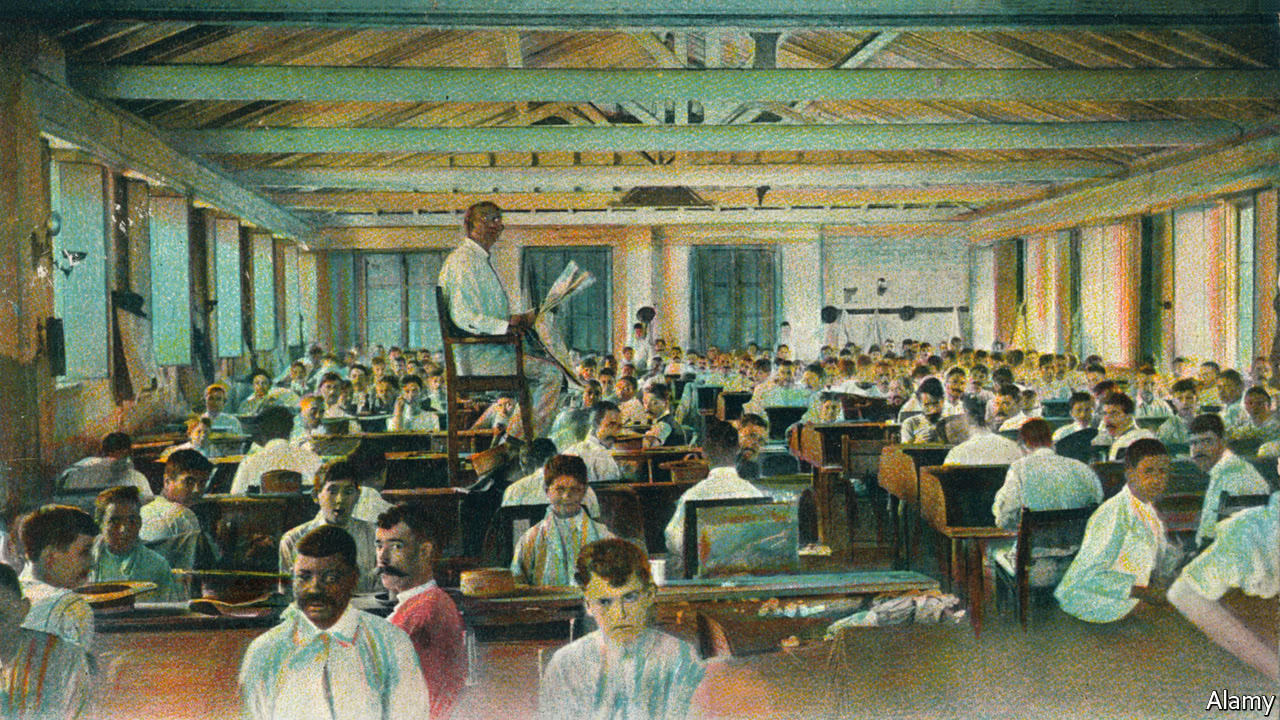

The ascetic, asthmatic Argentine doctor first fought alongside Fidel Castro in the mountains of Cuba’s Sierra Maestra. After the Cuban revolution had imposed communism on the island, Guevara left to try to “liberate” first Congo and then Bolivia. Those who idolise Che do so because they see him as an idealist who laid down his life for a cause. An aura of Christian sacrifice surrounds him.

That cause was “anti-imperialism” and ending exploitation by replacing it with “socialism” (ie, communism), Mr Morales declared this week. In this, Guevara was a man of the 1960s—he fomented revolution as yanqui bombers were napalming Vietnamese peasants and when it was still possible for many people to believe that only violence and communism could defeat expansionary American imperialism.

For the Latin American left, that vision has congealed into archaism. In Colombia it contributed to the destructive insurgency of the FARC, which ended only last year, and that of the ELN, an avowedly guevarist group, which declared a ceasefire last month. Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s president, justifies the crushing of opposition as an act of anti-imperialism. Mr Morales, who after 11 years in power shows no sign of being prepared to relinquish it, may yet try to do the same.

So occluded is the lens of anti-imperialism that much of the Latin American left has failed to detect that American meddling in the region largely ended with the cold war, and that most younger Latin Americans see the United States as a source of investment, opportunity and technological progress (or at least did so before the arrival of President Donald Trump). But old dogmas die hard. “La Cordillera”, a newly released Argentine film, portrays an American diplomat offering a massive bribe to a fictional Argentine president (played by Ricardo Darín of the Oscar-winning “The Secret in Their Eyes”). The inducement is to vote against a regional oil cartel proposed by a left-wing Brazilian leader. The film seems oblivious to the fact that Latin America has just seen something that is almost the reverse: companies close to a left-wing president in Brazil showering money to get friendly candidates elected in other countries and then paying bribes to win public contracts.

In Guevara’s view, equality was to be achieved by levelling down. As minister of industries in Cuba, he wanted to expropriate every farm and shop. True, Cuba offers its people reasonable health care and education, and helps them through hurricanes, but those achievements have come at the cost of miserable wages, the denial of opportunity and the brutal suppression of dissent. In Venezuela’s pastiche of the Cuban revolution, installed by the late Hugo Chávez, another Che fan, the masses have been impoverished while insiders have become fabulously and corruptly rich.

Guevara’s mistake was to deny the possibility of democracy, or the social progress it could bring, in Latin America. Most countries in the region are no longer controlled by a narrow oligarchy, nor under the yanqui thumb. Whatever their mistakes and failings, reformist governments in countries like Chile, Brazil and Colombia have shown that inequality, while still high, can be reduced by good policies. When Che first set foot in Cuba, it was one of the most developed countries in Latin America. Despite its investment in health and education, freer countries have now caught up and in some cases surpassed it.

By erecting anti-imperialism and equality as supreme values, too many leftists have been complicit in tyranny and corruption. They have shamefully refused to condemn Mr Maduro’s dictatorship in Venezuela. Not only does democracy offer the best hope of progress for the masses, it also protects the left against its own mistakes. It is long past time to bury Che and find a better icon.

In death Che, with his flowing hair and beret, has become one of the world’s favourite revolutionary icons. His fans span the globe. Youthful rebels wear T-shirts emblazoned with his image. Ireland this month issued a commemorative stamp. But it is in Latin America where his influence has been greatest, and where his legacy—for the left in particular—has been most damaging.

Latest updates

That cause was “anti-imperialism” and ending exploitation by replacing it with “socialism” (ie, communism), Mr Morales declared this week. In this, Guevara was a man of the 1960s—he fomented revolution as yanqui bombers were napalming Vietnamese peasants and when it was still possible for many people to believe that only violence and communism could defeat expansionary American imperialism.

For the Latin American left, that vision has congealed into archaism. In Colombia it contributed to the destructive insurgency of the FARC, which ended only last year, and that of the ELN, an avowedly guevarist group, which declared a ceasefire last month. Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s president, justifies the crushing of opposition as an act of anti-imperialism. Mr Morales, who after 11 years in power shows no sign of being prepared to relinquish it, may yet try to do the same.

So occluded is the lens of anti-imperialism that much of the Latin American left has failed to detect that American meddling in the region largely ended with the cold war, and that most younger Latin Americans see the United States as a source of investment, opportunity and technological progress (or at least did so before the arrival of President Donald Trump). But old dogmas die hard. “La Cordillera”, a newly released Argentine film, portrays an American diplomat offering a massive bribe to a fictional Argentine president (played by Ricardo Darín of the Oscar-winning “The Secret in Their Eyes”). The inducement is to vote against a regional oil cartel proposed by a left-wing Brazilian leader. The film seems oblivious to the fact that Latin America has just seen something that is almost the reverse: companies close to a left-wing president in Brazil showering money to get friendly candidates elected in other countries and then paying bribes to win public contracts.

In Guevara’s view, equality was to be achieved by levelling down. As minister of industries in Cuba, he wanted to expropriate every farm and shop. True, Cuba offers its people reasonable health care and education, and helps them through hurricanes, but those achievements have come at the cost of miserable wages, the denial of opportunity and the brutal suppression of dissent. In Venezuela’s pastiche of the Cuban revolution, installed by the late Hugo Chávez, another Che fan, the masses have been impoverished while insiders have become fabulously and corruptly rich.

Guevara’s mistake was to deny the possibility of democracy, or the social progress it could bring, in Latin America. Most countries in the region are no longer controlled by a narrow oligarchy, nor under the yanqui thumb. Whatever their mistakes and failings, reformist governments in countries like Chile, Brazil and Colombia have shown that inequality, while still high, can be reduced by good policies. When Che first set foot in Cuba, it was one of the most developed countries in Latin America. Despite its investment in health and education, freer countries have now caught up and in some cases surpassed it.

By erecting anti-imperialism and equality as supreme values, too many leftists have been complicit in tyranny and corruption. They have shamefully refused to condemn Mr Maduro’s dictatorship in Venezuela. Not only does democracy offer the best hope of progress for the masses, it also protects the left against its own mistakes. It is long past time to bury Che and find a better icon.