A Brazilian bribery machine

Record fine for illegal payments by Odebrecht raises hopes of end to the country’s culture of impunity

It revamped the Maracanã stadium, Brazil’s home of football in Rio de Janeiro, for the 2014 World Cup, developed one of the largest hydroelectric dams in Africa and built a $1bn port in Cuba. But now Odebrecht, Latin America’s largest construction group, is in danger of being better known for creating one of the biggest bribery machines in corporate history.

The US Department of Justice last week described the operation, which channelled almost $788m to politicians and officials across a dozencountries, as an “unparalleled bribery and bid rigging scheme” as it together with Brazilian and Swiss authorities slapped a record fine of at least $3.5bn on Odebrecht.

The scandal that has torn through Odebrecht and threatens to unseat senior politicians in Brazil and across the region had discreet beginnings in the company’s mundane sounding “structured operations” division.

It was there — a secret operation in full public view — that Maria Tavares, a secretary at the company, began her work day, she told prosecutors, by “downloading a spreadsheet that contained the [bribery] payments to be made for that week” — essentially a payroll for politicians and public officials stretching from Brasília to Maputo in Mozambique.

So sophisticated was the operation, which ran for at least a decade starting in 2001, that it used its own separate computer and email systems complete with code names for the payees, the payments — known as acarajés after a local fried bean cake — and the bag men who delivered the money. Odebrecht even set up its own, one-stop bribery shop by buying a bank in Antigua where the corrupt could open accounts and receive direct payments.

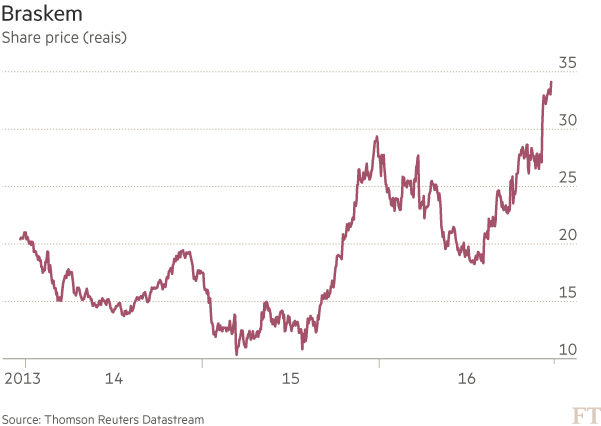

The revelations provided by Ms Tavares and others that Odebrecht engaged in “brazen” systematic international bribery were revealed as part of a plea bargain agreed with US, Brazilian and Swiss prosecutors last week. Odebrecht will pay at least $3.5bn for its wrongdoing, including a $957m fine for Braskem, its petrochemical arm.

Beyond the figures, the discovery that one of the most important companies in Latin America’s largest economy conducted such a crime for so long and in so many jurisdictions has shaken Brazil’s business establishment to its foundations.

“Never has the political and economic system been hit so profoundly,” Gilmar Mendes, a Brazilian Supreme Court judge, told the Financial Times.

With many of the payments made through legitimate banking systems, the scandal is also raising questions over global compliance requirements, particularly in the developing world, where Odebrecht paid off scores of senior public officials and was only undone by a determined investigation by Brazilian federal police and prosecutors with the support of crusading judges.

For the government of President Michel Temer and its efforts to revive Brazil’s economy the episode poses a threat. Brought to power in August after his predecessor, the leftist president Dilma Rousseff, was impeached for manipulating the budget, investors are depending on an ambitious reform agenda to rescue what was six years ago one of the world’s fastest growing economies from its worst recession in more than a century.

Aside from the plea bargain announced in the US this month, nearly 80 executives of Odebrecht, including its former chief executive and scion of the founding family, Marcelo Odebrecht, have filed detailed witness testimonies — that are yet to be made public — with Brazil’s Supreme Court.

Leaks to Brazilian media have claimed that Mr Temer and senior figures in his ruling Brazilian Democratic Movement party have been implicated in some of the testimonies of these plea bargains. They deny wrongdoing.

Alongside the wider probe into corruption by construction groups and politicians at state-owned oil company Petrobras, known as lava jato (car wash), the Odebrecht investigation is changing the culture of impunity in Brazil.

“Popular pressure is very strong in Brazil these days and no one can really stand corruption any longer,” says Sérgio Lazzarini, an author of books on crony capitalism in Brazil. “Everyone has the sensation we have been robbed all these years.”

Presiding over expansion

If one man summed up the sense of impunity that used to pervade Brazil, it was Marcelo Odebrecht. Barely into his 40s, he assumed the leadership of the conglomerate founded by his grandfather Norberto Odebrecht, a descendant of German immigrants to Brazil, in 2009. The group employs 128,000 people of 70 nationalities and operates projects ranging from ports, dams, metro networks, highways and a nuclear submarine base in countries such as the US, Angola and Panama. It was one of Brazil’s first multinationals, with 58 per cent of its operating income coming from offshore.

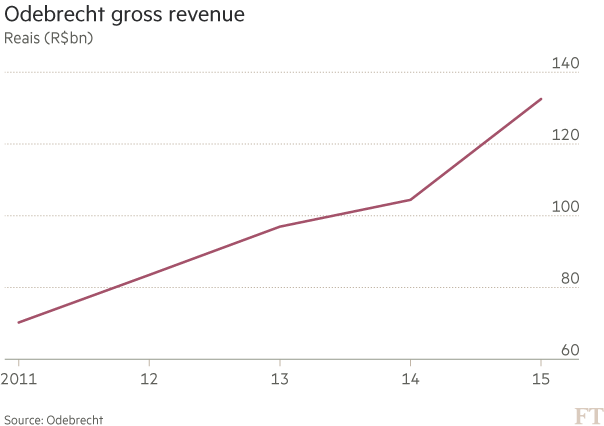

It prospered under Marcelo’s leadership and under the leftist governments of the Workers’ party, or PT. In the years following the re-election in 2006 of former PT president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, himself now a defendant in the Petrobras political funding scandal, Odebrecht’s gross revenue increased nearly sixfold to R$126.6bn($38.6bn) for the 12 months ending June 2016.

An exercise fanatic who reportedly was such a workaholic he had to make notes in his calendar to remind himself to give his wife Bela and their three children a hug, Marcelo kept a hectic schedule. He would host heads of state from the developing world while plotting with his lieutenants how to influence various political contacts and manipulate bills going through congress to benefit Odebrecht and Braskem, according to court documents. He was particularly close to Mr Lula da Silva. He and his father Emílio Odebrecht regularly travelled with the former president, who has denied accusations of receiving favours from the company, around Africa and Latin America to meet world leaders.

Sense of invulnerability

When the Petrobras scandal first broke in 2014 it exposed the nexus between big business and the illicit funding of political parties and should have sent shivers around Odebrecht. It involved a cartel of construction companies that collaborated with Petrobras executives and politicians to exchange bribes and kickbacks for contracts.

The investigation has led to 82 people — ranging from former PT treasurer João Vaccari Neto to Marcelo Odebrecht himself — being convicted in the lower courts on charges ranging from corruption to money laundering while the Supreme Court, which is responsible for trying serving politicians, is processing a further 74 cases.

And yet such was the sense of power at Odebrecht that Marcelo and his executives did not panic when prosecutors began probing Petrobras.

One associate remembers a meeting early in the investigation to discuss a loan in which the former Odebrecht chief became indignant when asked about the investigations and insisted it was all a plot to get at him and the PT-led government. Marcelo seemed confident until the end in his ability to subvert the probes, discussing strategies for doing so with his senior executives, according to prosecutors. He even paid €3m to a “high official” in Antigua in exchange for the official refusing to provide information on Odebrecht to Brazilian authorities, according to the plea bargain lodged in the US.

Indeed, for a long time, Marcelo seemed untouchable. But then in February 2015 the Petrobras scandal reached his door when a former executive at the energy company, Paulo Roberto Costa, told prosecutors he had received $31.5m in bribes from Odebrecht paid into a Swiss account. In June that year federal police swooped in an operation they called Erga Omnes — a Latin term signifying that the law applies equally to everyone. They arrested Marcelo and seized 11 mobile phones from his home. As they dug deeper, they discovered the remarkable extent to which the Odebrecht group had gone to run its parallel payments network.

In March this year, Marcelo was sentenced to 19 years in jail for corruption and other charges.

After his arrest Marcelo initially denied any wrongdoing. But the growing weight of the evidence, including Ms Tavares’ revelations about the structured operations unit, coupled with the troubled financial condition of the group, which is struggling to secure loans even as its construction arm suffers a one-third contraction in new business, forced him to negotiate the plea bargain that led to this month’s settlement with the US, Brazilian and Swiss governments.

In exchange for providing testimony to the Supreme Court, Marcelo and the nearly 80 executives of his company involved in the plea bargain will be given leniency. While a relief for Odebrecht and its former chief, who could be released early from prison, the plea bargains are causing fresh tremors in a Brazilian political scene battered by the Petrobras scandal.

Newspapers this month detailed leaked testimony from Marcelo and another Odebrecht executive alleging that Mr Temer had sought political donations worth R$10m in May 2014 ahead of presidential elections that year. Mr Temer, who wasMs Rousseff’s vice-president, has denied any wrongdoing.

The leaks have sparked concerns about Mr Temer’s survival as president. The economy is showing few signs of life, shrinking at an annual rate of nearly 3 per cent in the third quarter. A poll by Pulso Brasil last week showed that 15 per cent of those surveyed approved of Mr Temer while 77 per cent disapproved.

But analysts argue that unlike Ms Rousseff, he has the markets and congress on his side. Where she alienated investors by backtracking on promises to rein in budget deficits, Mr Temer has pushed through a constitutional amendment freezing expenses in real terms for up to 20 years and has started difficult pension reforms. Ironically, his lack of popularity is leading him to try reforms few others have had the courage to attempt, say analysts.

“The paradox is that a highly unpopular government that therefore has little to lose has turned out to be a government that acts with conviction and in a pragmatic way,” says Fernando Schüler, a political scientist at Insper university in São Paulo.

‘Inevitable reform’

With the plea bargain payout, Odebrecht, which will struggle to pay the $3.5bn, has promised to turn over a new leaf. The structured operations division has gone. Ms Tavares told prosecutors how one day in August last year, she was suddenly sent to another division of Odebrecht. The structured operations division was “closed, there was not one person left there”, she said, and two of the most senior staff fled to Miami.

The question is whether the Odebrecht plea bargain and the car wash probe will mark an end to the endemic corruption affecting Brazil.

Many analysts argue corruption will not be wiped out until there is sweeping reform to lower the cost of political campaigns and reduce the incentives for graft. Brazil’s system allows an extreme number of parties — currently 35 in all — most of which exist only to extract rent from the system, analysts say. But the Odebrecht scandal and the car wash investigation have at least finally put the need for these reforms at the top of the political agenda, analysts say.

Mr Mendes, the judge, says: “I think [the car wash probe] has had this virtue: it has made reform of the system inevitable.”